Published 16:00 IST, January 2nd 2025

Trading Disruptors Will Mimic Banks And Beat Them

Electronic market-makers like Jane Street and Citadel are evolving into bank-like entities, expanding into bonds and commodities while targeting institutional

- Opinion

- 4 min read

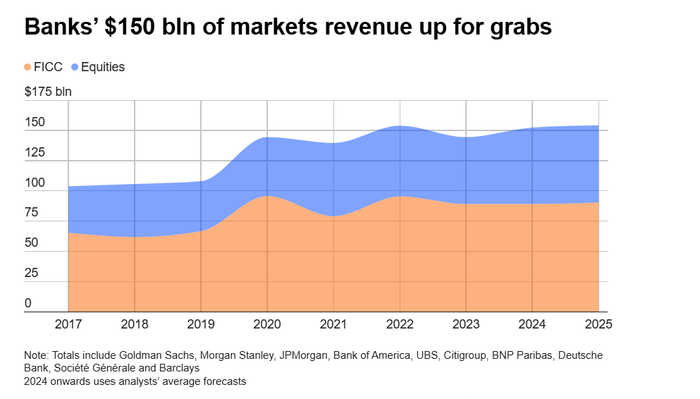

Sometimes the danger to an incumbent business comes as a bolt from the blue. At other times, it approaches with a familiar face. That’s the case for trading giants like JPMorgan, Morgan Stanley, Bank of America and Deutsche Bank, who in 2025 will notice electronic market-makers acting more like banks. The trend is exemplified by Jane Street’s gargantuan balance sheet, and Citadel Securities’ hiring of veteran Goldman Sachs banker Jim Esposito. The shift puts a much bigger slice of the $150 billion global-markets pie at risk.

Banks and non-banks have lived side-by-side in the equities and fixed-income businesses for years. Specialist market-makers like Jane Street, XTX Markets and Citadel, which is distinct from the hedge fund of the same name, filled the space that banks left after the 2008 crisis. Known as high-frequency traders, they thrived by filling orders quickly over public exchanges and other electronic venues. The secret sauce is a combination of slick IT systems and sophisticated analytics, allowing them to exploit narrow gaps between securities’ buying and selling prices.

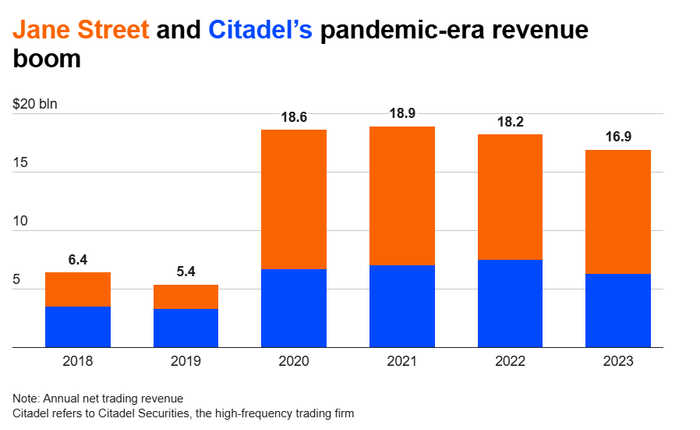

The trading industry has proved big enough to accommodate banks and non-banks. In 2020, for example, Jane Street and Citadel’s combined net revenue more than tripled, but banks’ trading income still rose by a third. The relative newcomers traditionally focus on high-volume, low-value orders in widely traded markets, like exchange-traded funds and stocks. Jane Street is the lead market-maker for 20% of U.S. ETFs, an employee said in late 2023, while Citadel reckons it handles 23% of the overall U.S. equity market volume.

Banks typically lack the IT skills to compete with the specialists in such low-margin businesses, dubbed flow trading. And they have been relaxed about giving up market share because they make most of their money executing large or complex trades for big money managers and companies. Banks will typically handle a hedge fund’s flow to win its prime-brokerage custom, for example, or execute an asset manager’s stock orders to secure more lucrative derivative business.

The seemingly happy co-existence will end in 2025, however. The first reason is that the upstarts are making a fresh assault on bond and commodity trading, an area that has been hitherto relatively immune to competition. Citadel under CEO Peng Zhao is pushing more aggressively into fixed-income markets like European government debt. It will soon start trading baskets of bonds for clients, according to a person familiar with the matter. The plan is to form a beachhead in investment-grade credit and global rates, and subsequently grow into other areas. Jane Street is already a bond ETF giant, giving it an angle to push more aggressively into new markets.

The second problem for the banks is that electronic market-makers’ prodigious profits have given them a giant capital base. Jane Street’s “members’ equity”, mostly retained earnings on the balance sheet, is about $24 billion, the Financial Times reported. That’s about half the average allocated equity in Citigroup and Bank of America’s markets businesses, though the incumbents’ resources are spread more thinly. The upshot is that high-frequency traders increasingly have the flexibility to do bank-like things, like holding exposures for hours or days rather than just seconds or minutes, in theory giving them access to a bigger slice of the market-making pie.

What’s even scarier for the banks is that Citadel seems to be trying to serve the needs of large institutional clients, rather than just picking off small trades. Take its 2024 hiring of Esposito as president, whom rivals fear as someone capable of opening doors with major asset managers and even corporate clients. Citadel is even considering launching something akin to banks’ equity research product, according to a person familiar with the matter, potentially winning its salespeople more time in front of BlackRock, PGIM and others.

In response, banks will have to invest more in technology to keep market share. That’s easier for the likes of Goldman, Bank of America and JPMorgan than it is for the next tier down, like Barclays. Relative minnows like Société Générale will struggle even more.

It’s not clear that many of the banks’ trading divisions can afford to take much of a hit. The relevant business for Bank of America, which is one of the few groups to break out its markets results separately, will generate a return on equity of about 13% in 2025, based on Visible Alpha consensus data. Other, smaller businesses are probably barely in the double digits, if at all. A resurgent trading threat may be the killer blow.

Updated 16:00 IST, January 2nd 2025