Published 14:24 IST, September 16th 2024

The European Union risks a sad, bad future

There are potential fixes such as the plan former European Central Bank boss Mario Draghi set out last week.

- Opinion

- 6 min read

Sad and bad. The European Union brought peace and prosperity to a troubled region in the decades following World War Two. But it may lack energy and become impotent in the decades ahead.

Not only is the EU economy stagnating. The bloc may also be bullied by Russia, China and even the United States. While there are potential fixes, such as the plan former European Central Bank boss Mario Draghi set out last week, the EU and its members are unlikely to implement them. It’s a sad, bad future.

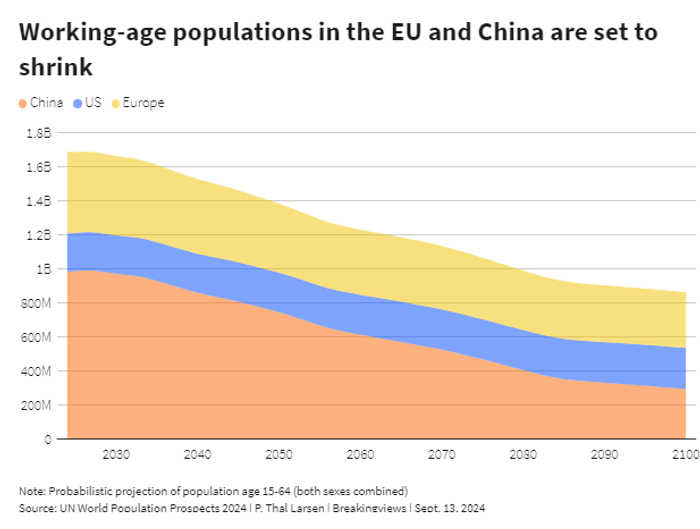

The sad part of the prognosis is economic stasis. EU productivity has grown on average only 0.7% a year since 2015. Combine that with a shrinking working-age population and the economy will stall, Draghi concluded in a report the European Commission, the bloc’s executive arm, asked him to produce.

The bad bit is that a moribund EU is easier for more powerful countries to push around. Russia poses a military threat, especially if the Kremlin wins its war in Ukraine. The danger from China and the United States, whose economies are growing more rapidly than the EU’s, is commercial.

If Donald Trump wins the U.S. presidential election in November, the risks to the EU will be acute. The Republican nominee could not even bring himself to say he wanted Ukraine to win the war with Russia in last week’s debate with his Democratic rival Kamala Harris. He has also threatened to impose tariffs on allies as well as China. And if the EU and the United States engage in a trade war, there’s little chance of them joining forces to stand up to Beijing.

A blueprint

Draghi has a blueprint to revitalise the EU. He wants the region to invest an extra 800 billion euros a year, equivalent to nearly 5% of its output. Much of this would fund an industrial policy to compete with the United States and China, with an emphasis on clean technology and high-tech sectors such as artificial intelligence.

The EU would also boost its defences to meet the threat from Russia. The bloc’s armaments industry suffers from fragmentation. Europe operates 12 different types of tank, while the United States makes only one.

Germany’s defences are in a particularly parlous state, according to a separate report by the Kiel Institute published last week. Russia is now able to produce as many weapons in six months as all of Germany’s armed forces currently field.

Draghi also wants the EU to take a more joined-up approach to economic statecraft. He recommends that industrial policy should dovetail with initiatives to prevent unfair competition from China and policies to secure alternative supply chains of critical products and materials so that the EU is not overly dependent on the People’s Republic.

The action plan does not end there. The former Italian prime minister also calls for improvements to the bloc’s single market to increase productivity growth and reforms to the EU’s governance to prevent the region’s 27 member states from vetoing so many initiatives.

While his proposals are laudable, the political conditions are not ripe to implement them. This is because the most ambitious initiatives – covering finance, foreign policy, defence and governance – require unanimous approval by the EU’s member states.

When Germany and France, the two largest countries, have strong governments, they can cooperate with the Commission to embody the EU-wide interest and persuade smaller countries to adopt new initiatives, says Marco Buti, a former senior EU official. But that’s not the case now. Both German Chancellor Olaf Scholz and French President Emmanuel Macron are politically weak.

What’s more, both leaders are contending with popular far-right and far-left parties at home that are unenthusiastic about the European project. The irony is that if the EU cannot get its act together it will suffer, further stoking support for extremist parties.

Where’s the money?

It is also hard to see how the region could raise an extra 800 billion euros a year for investment. In theory, the EU could borrow some of it. But Germany’s finance minister shot down the idea within hours of Draghi proposing it.

National governments will not find it easy to find the cash either. France and Italy are already drowning in debt. Meanwhile Germany has a law, the so-called debt brake, which severely constrains how much its government can borrow.

The private sector could, in theory, provide the lion’s share of the money. But the European Commission and International Monetary Fund expect that an extra 5% of GDP going into investment would boost the economy by only 6% after 15 years. That’s not a great payback.

For the investment to flow in the required quantities, the private sector’s cost of capital will need to fall by about 2.5 percentage points, according to the Commission’s modelling. So the public sector will have to provide fiscal incentives – which pushes the issue back to EU or national budgets.

Fingers crossed

The EU’s prospects aren’t all gloom and doom. For a start, next year’s federal elections in Germany might produce a strong centre-right government able and willing to reform the debt brake. The EU’s largest economy could then borrow money to improve its defences and boost investment.

More optimistically, Germany could soften its opposition to more borrowing at the EU level. The bloc might then have the firepower to implement part of Draghi’s plan, says Jean Pisani-Ferry, senior fellow at the Bruegel think tank.

A victory by Harris in the U.S. presidential elections may also take the heat off the EU, especially if it stops Russia from crushing Ukraine. A Democrat in the White House would also be less likely to threaten the EU.

What’s more, the Chinese economy could stagnate in the next decade or so, says Erik Nielsen, UniCredit’s chief economic adviser. It is already running into multiple headwinds and its working-age population will fall much more rapidly than the EU’s in coming decades. While a less dynamic People’s Republic would buy fewer of the bloc’s exports, Beijing would also be less capable of bullying Brussels.

Keeping one’s fingers crossed is not the same as having the bold strategic plan that Draghi advocates. But it may be the best the EU can manage.

Updated 14:24 IST, September 16th 2024