Published 12:08 IST, October 8th 2024

Ireland spins global tax mess into $28 bln of gold

The Irish government on Oct. 1 announced 10.5 billion euros of tax cuts and spending increases for 2025.

- Economy

- 5 min read

Haven on earth. Jack Chambers has an unusual problem for a finance minister: too much money. The Irishman last week said he expected a 24-billion-euro budget surplus in 2024, thanks to an Apple back tax bill and ballooning receipts from other large U.S. multinationals.

If recent efforts to clean up the global corporate tax system had worked, Chambers’ happy predicament shouldn’t be possible. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development brokered a landmark deal in 2021, which was supposed to reduce the incentives for corporate profit shifting to low-tax countries like Ireland, and end the race to the bottom on global rates. Luckily for Dublin, there’s little sign of anything changing.

Ireland’s bulging coffers this year are, admittedly, unusual. The surplus that Chambers plans to start divvying out is due in large part to a European court ruling that forces Apple to hand about 13 billion euros to Dublin, in recompense for what Brussels characterises as a sweetheart historic tax deal. Yet Ireland, which didn’t want the money, would still be comfortably in surplus without the iPhone maker’s cash. The International Monetary Fund expects the Emerald Isle to have a positive budget balance for many years.

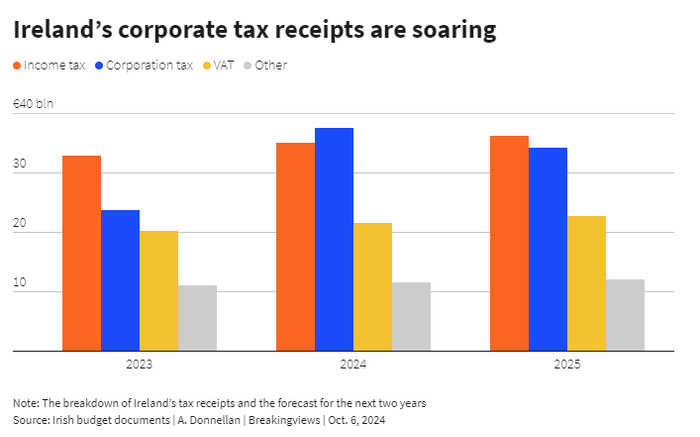

And it’s clear that Ireland is an international outlier. Its headline rate for businesses is just 12.5%, compared with a worldwide average of 23% according to the Tax Foundation. That gap has drawn U.S. giants, who often declare an outsized proportion of their international profit in the country. Corporation tax brought in more than a quarter of overall government receipts in 2023, compared with less than a tenth in Britain.

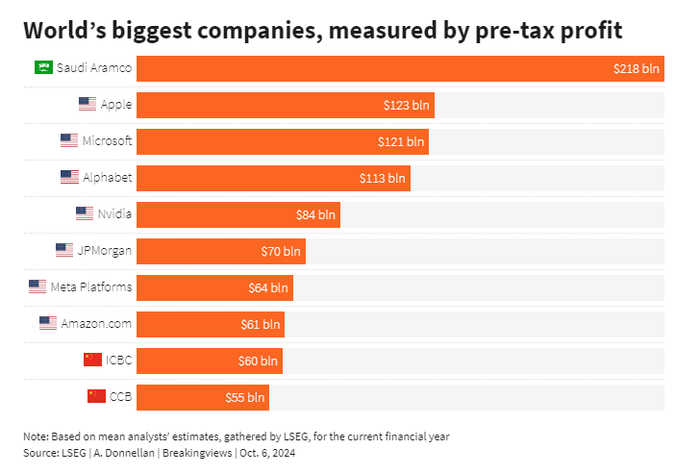

The Irish Fiscal Advisory Council said that in 2022 just 10 large companies accounted for 60% of corporation tax receipts, with three of the firms contributing one-third of the total haul. The independent fiscal watchdog didn’t name the companies, but the list likely includes some of the U.S. giants with large presences in cities like Dublin or Cork, including Apple , Google owner Alphabet, Facebook owner Meta Platforms, drugmaker Pfizer and chip group Intel.

The rest of the world has tried to make life harder for Ireland. The OECD-brokered agreement, initially signed three years ago, had by June 2023 attracted 139 signatories, including all of the world’s major economies. It had two elements. The first was a new digital taxing principle that empowered countries to charge levies based on where revenue gets generated, rather than where a company bases its operations. In theory, that would allow France or Germany to claim some money from Meta or Alphabet, even if the companies reported scant profit to Paris or Berlin.

The second element was a new so-called “minimum tax” of 15%, which in theory should remove the incentive for tax havens to charge anything less than that level. The OECD estimated that total profit booked by large companies in low-tax jurisdictions, defined as countries with a sub-15% rate, should fall by 80% as a result, implying that corporate tax avoidance would be mostly solved.

As Chambers’ bumper budget shows, that clearly hasn’t happened. One big problem for the OECD effort is that the United States hasn’t implemented the minimum tax. Because so many of the world’s biggest companies are from the United States, but currently declaring much profit abroad, the system as envisaged doesn’t work without U.S. involvement. And with a divided Congress seeming likely after the November elections, it’s hard to see much changing on that front.

Another difficulty is that 15% is barely above Ireland’s 12.5% rate. The implication is that a new minimum tax, even if implemented globally, might not change companies’ incentives all that much. According to a person involved in the OECD negotiations, Dublin managed to have the words “at least” removed from the agreement, suggesting that the global rate might stay at a level that Ireland can live with.

The other leg of the OECD plan is also bogged down. The new digital taxing right is supposed to allow governments to get money out of technology giants with no local physical presence. But so far, countries cannot agree on how those rules should be implemented. Again, U.S. intransigence is a problem. Recent estimates from the Joint Committee on Taxation suggest that this plank of the OECD reforms could see the United States lose $57 billion in tax revenue over 10 years. That’s a hard sell to any administration. And absent a deal on that front, countries like France and Spain are likely to stick with pre-existing national digital taxes instead, prompting a further tit-for-tat with Washington that would ultimately leave Ireland’s current share of the pie untouched.

In theory, Ireland’s European neighbours could pile some pressure on Chambers and Prime Minister Simon Harris. Brussels has in the past talked about bloc-wide digital levies and other measures that could dent Dublin’s low-tax appeal. It’s possible that growing fiscal problems in France and elsewhere could finally force the rest of the European Union to lose patience with Ireland. But successful EU-wide tax measures are rare, and it’s not clear that Brussels has many other ways to bring Dublin into line.

The upshot is that Chambers and Harris can probably rest easy. The Irish government must call an election before March 2025, which makes it a good time for them to have lots of spare money sitting around. Good uses of the funds include investing to solve the country’s chronic housing shortage or building an underground metro service in Dublin. Splashing the cash is likely to anger hard-up neighbours. But with the OECD process still stuck in the weeds, it’s not clear why Chambers should care.

Context News

The Irish government on Oct. 1 announced 10.5 billion euros of tax cuts and spending increases for 2025. The budget also included longer-term plans on the use of a 14-billion-euro back tax bill from Apple to improve the country’s infrastructure. The Apple back taxes are set to push Ireland’s surplus this year to 7.5% of gross national income, according to the government. The figure will fall to 2.9% in 2025.

Updated 12:08 IST, October 8th 2024