Published 10:37 IST, July 29th 2024

India’s water stress is a growing sovereign risk

Too much and too little water routinely affects everything, from cities to power plants to farming.

- Opinion

- 3 min read

Watered down. The world’s fifth-largest economy faces a fundamental risk to growth: water security. Erratic rainfall of late is one reason why India's Ministry of Finance now reckons GDP growth will slow to 7%, if not lower, in the 12 months to the end of next March, from 7.8% in the previous year. Too much and too little water routinely affects everything, from cities to power plants to farming. Climate change and weak state capacity make it worse. Yet, this rising problem is usually either underappreciated or ignored.

The crisis takes on plenty of forms: political disputes over sharing rivers; inefficient irrigation techniques; inequitable drinking-water access; flooding in cities including New Delhi and Mumbai; and more. The drowning of three students after rainwater entered a basement library in the capital on Saturday is only the latest in a series of water-linked mishaps.

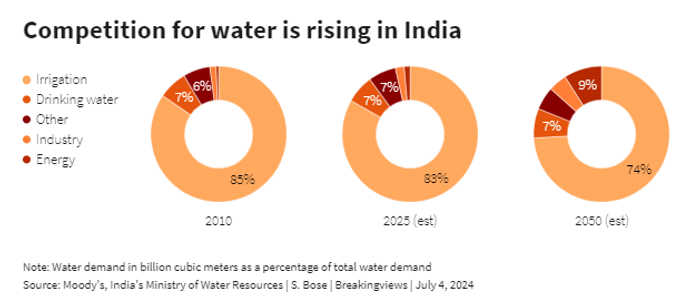

Shortages are as potent as deluges. Rating agency Moody’s in June identified water security as a sovereign credit risk to India and a significant threat to businesses like coal-fired power stations and steelmakers. Changing monsoon patterns hurt farm incomes and rural consumption.

Between 2013 and 2016, water shortage-induced shutdowns cost India’s thermal power-dependent utilities over $1.4 billion in lost revenue, the World Resources Institute found in 2018. The climate nonprofit calculated that for the largest of them, rising demand from other water users will, by 2030, increase competition for the resource by, on average, up to 28%. Saltwater incursion and groundwater depletion hurt farm output and force villagers to leave, usually to cities. An official survey in 2021 found water scarcity to be among the top reasons for internal migration among working Indians.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s administration has taken some steps. It has set a target of cutting freshwater extraction to less than 50% by 2030 from 66%, the highest rate in the world, Reuters reported on July 4, citing an official document. It also plans to more than triple wastewater recycling to 70% over the same period. Those are steep goals, not least because India’s federal structure gives states first dibs on legislating water issues. Yet, there’s little evidence plans to build roads, bridges and other infrastructure account for the rising incidences of water-linked shocks.

The problem is not top of investors' minds. India’s vulnerability to climate change came up only briefly as a medium-term risk in Goldman Sachs’ conversations about the country with clients in Hong Kong and Mumbai, the bank said in a note on July 1. That’s partly because there are not enough data to quantify the threat, which is too often used as an excuse for inaction. It's time to change that.

Updated 10:37 IST, July 29th 2024