Published 14:44 IST, November 5th 2024

Saudi megafund’s success rests on fuzzy local bets

Saudi Arabia’s Future Investment Initiative took place in Riyadh between Oct. 29 and Oct. 31.

- Markets

- 6 min read

A big PIF. Saudi Arabia’s main mission is to diversify its heavily oil-dependent economy. But that “Vision 2030” project is undergoing a transition of its own. The kingdom’s $950 billion Public Investment Fund (PIF), tasked by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MbS) with delivery, is increasingly focused on a collection of relatively young domestic firms. While this segment’s value now exceeds $250 billion and is growing rapidly, the PIF’s dual mandate of boosting profits and jobs looks tough.

Since MbS started expanding the investment vehicle in 2016, the PIF has made a string of high-profile global bets, like committing $45 billion to SoftBank chief Masayoshi Son’s first Vision Fund, bankrolling a new golf tour, and making contrarian punts on Western blue-chip stocks during 2020 lockdowns. It has also made outlandish plans for flashy “giga-projects” to lure foreign tourists and businesses, the most notorious of which is NEOM – an entire new region in the northwest of the kingdom intended to feature a futuristic 170-kilometre-long city known as The Line.

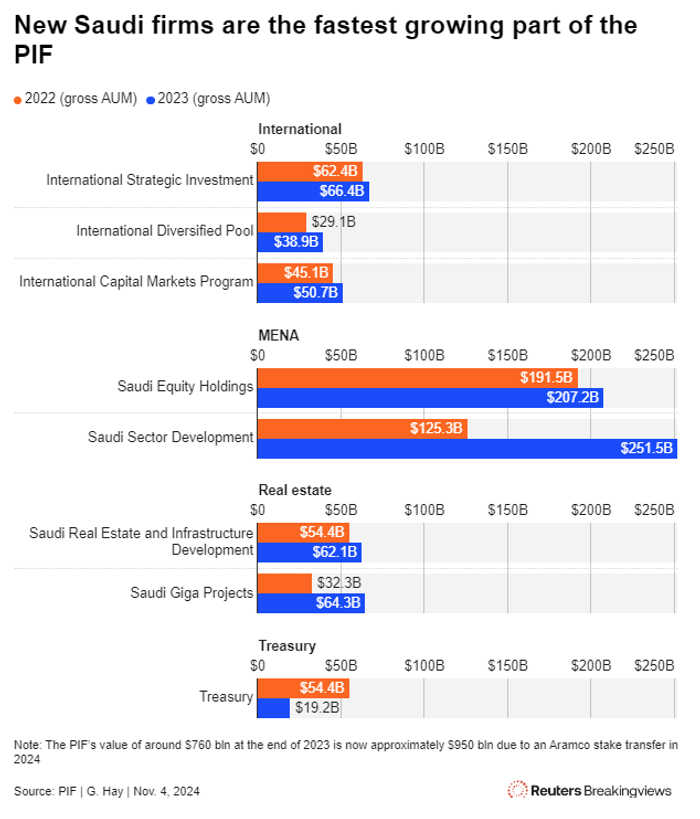

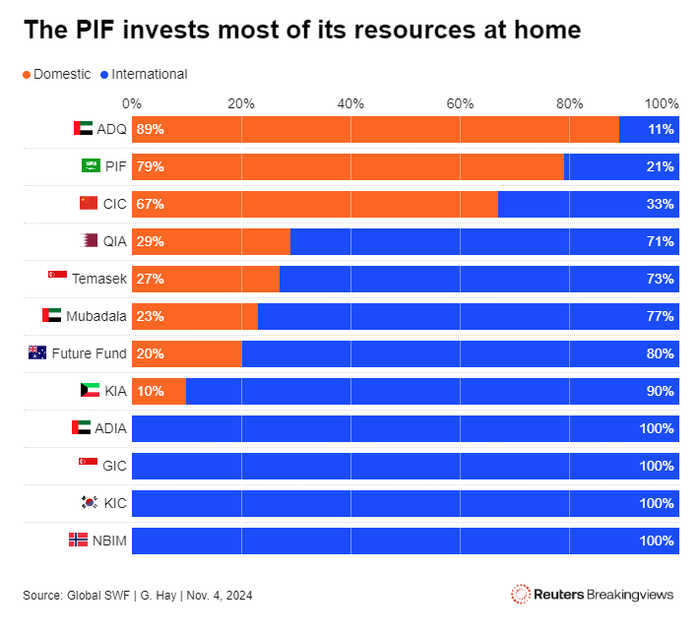

Yet drill down into what PIF actually is today, and it’s clear that the vehicle’s Governor Yasir Al-Rumayyan has a different focus. The overseas investments, like Newcastle United Football Club and Uber Technologies, collectively amounted to just 20% of assets, or $156 billion, at the end of 2023. Despite the massive spending required to complete the giga-projects, the total investments in that segment and the wider real estate and infrastructure unit amounted to $126 billion, or just 17% of PIF’s assets under management (AUM).

By far the largest portion of the vehicle’s investments, by contrast, sat at home. One bucket, called Saudi Equity Holdings, accounted for 27% of AUM and owned stakes in established listed companies like Saudi Telecom and Saudi National Bank. That was before the government this year transferred 8% of oil giant Aramco into the PIF, which altered the numbers.

The other, much faster-growing segment is called Saudi Sector Development. The division houses about 100 homegrown companies with a paper value of $251 billion as of December, or one-third of total AUM, making it by far the PIF’s biggest division in 2023. The companies include everything from unlisted sports and leisure startups to mining and healthcare groups.

This segment is halfway between a startup incubator and a private equity portfolio. Even more strikingly, its valuation doubled between the end of 2022 and 2023, making it comfortably the fastest growing part of the PIF. According to a person familiar with the matter, the majority of this spike came from the vehicle’s decision to deploy new capital, rather than a paper valuation uplift.

Riyadh’s Future Investment Initiative last week was full of these shiny new companies, which include startups selling Saudi’s distinctive brand of camel-milk ice cream and those focusing on female wellness. Many have hired noted foreign CEOs, attracted by the chance to deploy a ton of cash. SURJ Sports Investments, which is behind the UFC rival Professional Fighters League, is now headed by former Australian soccer executive Danny Townsend. Riyadh Air, an entirely new flagship carrier intended to help ferry 150 million tourists to Saudi by 2030, has secured the services of former Etihad boss Tony Douglas. And Savvy Games, which in 2021 secured $38 billion from PIF to invest in the gaming and e-sports sectors, is led by former senior Activision Blizzard executive Brian Ward.

Assessing the current financial health of these entities is complicated by their youth, and limited disclosure. The aggregate numbers imply an average valuation of about $2.5 billion per company, which seems a stretch given the nascent stage of many of the firms. But it’s likely that at least some are making headway. Savvy Games, for example, last year completed the $4.9 billion acquisition of U.S. mobile gaming group Scopely. Given that the target’s “Monopoly Go!” game has generated $3 billion of revenue in little more than one year, the company may already be worth multiples of the purchase price, since gaming peers like Electronic Arts trade on enterprise values of as much as 5 times sales.

Yet building homegrown stars by throwing money at companies is tough. Just ask SoftBank’s Son, whose Vision Fund 1 experienced underwhelming returns despite a $100 billion pot to spend. A bigger headache is that Rumayyan is not being judged solely on financial performance. All the portfolio companies have a second mandate to develop employment and economic demand across 13 sectors in their home country. Vision 2030 requires 65% of economic activity to stem from the private sector, against 48% as of last December. That gives PIF executives like Rumayyan, and national development division head Jerry Todd, a tough job.

Saudi faces major problems with a domestic education system that doesn’t churn out enough skilled young people, and a business environment that still often hinges on personal connections, rather than merit. Savvy Games exemplifies how international scale and local employment heft don’t necessarily yet go together. Saudi’s young population seems like a good match for the gaming sector, but only 80 of Savvy’s 3,500 staff are based in the kingdom, and only 30 of them are actually Saudi.

Nor does the Gulf state have limitless resources. The country’s finance ministry is projecting a 3% fiscal deficit even in 2027. The Saudi government does have $445 billion of net foreign assets on top of its PIF wealth. But a substantial drop in the price of oil, which provides 62% of state revenues, would limit Riyadh’s ability to keep topping up the state fund. Government debt is admittedly only 27% of GDP , offering room to borrow, but issuing bonds to pour into local startups seems like a risky move.

That backdrop will factor into the thinking of senior PIF types like Todd, especially since the fund is starting to nail down its strategic priorities for the five years from 2026, according to a person familiar with the matter. Saudi Finance Minister Mohammed Al-Jadaan has already hinted at possible changes to the pace of giga-project plans. Bankers at the FII conference also expected Riyadh to rein in breakneck construction plans, like hotels, in case the hoped-for tourist boom fails to materialise.

All of which leaves Rumayyan’s local corporate bets in a potentially tricky position. They’re essentially carrying the hopes of the government, but with an arguably vulnerable source of funding and a domestic labour force and demand that remain unknown quantities. If the local stars do no more than flicker, neither the outcomes nor the returns will look pretty.

Context News

Saudi Arabia’s Future Investment Initiative took place in Riyadh between Oct. 29 and Oct. 31.

Updated 14:44 IST, November 5th 2024