Published 10:37 IST, October 11th 2024

Direct lenders’ golden moment is over

The size of the median loan rose nearly five-fold between 2014 and 2021, the AIC reckons, as the industry’s largest funds jumped on beefy leveraged buyouts.

- Markets

- 6 min read

After the gold rush. The downside of having a “golden moment” is that things can only get worse. That’s what direct lenders, or the core of the private-credit world that focuses on buyout debt, are finding little more than a year after Blackstone President Jon Gray pronounced a heyday for non-bank credit providers writ large. The forces that boosted direct lending to roughly $850 billion in assets under management by the end of 2023, using Preqin figures, are waning. It spells lower returns and partnerships with banking frenemies.

In the pandemic’s wake, specialists like Blue Owl Capital, Ares Management and diversified giants like Blackstone and Apollo Global Management took a bite out of the traditionally bank-dominated leveraged finance business. Direct lenders’ share of loans to highly indebted companies, including those owned by private equity, grew from 7% in 2018 to 17% by mid-2023, according to JPMorgan.

The size of the median loan rose nearly five-fold between 2014 and 2021, the American Investment Council reckons, as the industry’s largest funds jumped on beefy leveraged buyouts like Hellman & Friedman and Permira’s $10 billion acquisition of Zendesk. And because direct lenders typically use floating rates, yields surged as central banks hiked. The net return on Ares’s Senior Direct Lending Fund II rose from 10% at the end of 2022 to 15% a year later, roughly the level typically targeted by private equity funds.

But the heyday had as much to do with competitors’ weakness as direct lenders’ strength. In 2022, Wall Street players like JPMorgan, Bank of America and Barclays got stuck holding $80 billion of mostly buyout debt. That predicament, a product of fast-rising rates, ran counter to the banks’ favored model of quickly selling loans to investors. It clogged up Wall Street balance sheets, giving private players free rein. As a result, about three-fifths of buyouts in 2023 relied on direct lenders, according to consultancy McKinsey.

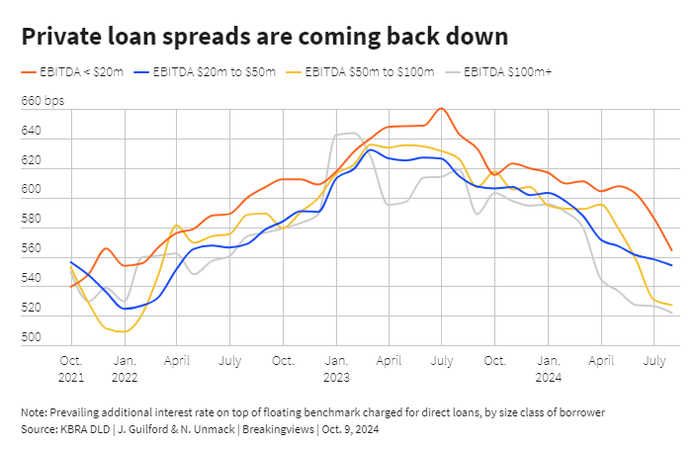

Now, however, loan and bond markets have recovered thanks to central-bank rate cuts and the absence of a recession. Deal-starved credit investors, like collateralized loan obligations, are hungry again. Public loan markets financed a larger share of buyouts by volume than private credit funds did in the three months to September, reckons PitchBook LCD. Renewed competition from banks means direct lenders are having to offer lower rates. For private loans to large borrowers, the spread over benchmark rates fell from 6.4 percentage points in early 2023 to 5.2 percentage points this July, according to ratings firm KBRA.

Direct lenders aren’t just losing out on new deals. Borrowers who had turned to private markets during the golden era can now refinance at a lower cost in public markets, and so are able to play the two markets off against each other. Some $22 billion of these refinancings happened this year in the U.S. alone, PitchBook LCD data shows. Examples in Europe include French insurance broker April, which issued a public loan at a spread that was 2.5 percentage points lower than the private borrowing it replaced. To hold onto business, direct lenders are having to accept lower rates. Italian pharmaceutical group Doc Generici managed to slash the coupon on a recent refinancing deal with HPS and Blackstone, after banks tried to lure it away.

Admittedly, direct lenders have some advantages that will endure, including greater speed, certainty and goodies like so-called delayed-draw loans, which borrowers can use to fund future acquisitions. The non-banks also provide more leverage than regulation-constrained Wall Street players – typically up to a turn of EBITDA.

Finally, direct lenders can back companies with minimal free cash flow by measuring debt against recurring, sticky revenue. That gives them the run of deals involving fast-growing software groups, like the Blue Owl-led package for Smartsheet’s recent buyout. Meanwhile, those who have stayed focused on smaller borrowers too little to avail themselves of a syndicated alternative, like Bain Capital's lending arm, are still seeing the highest spreads.

Direct lenders and banks can work together. Take the possible $17 billion buyout of Sanofi’s consumer division. If it happens, that deal may rely on banks offering senior debt and private lenders providing riskier junior loans, together bringing leverage to around 7 times EBITDA, according to a person familiar with the matter. Pricing subordinated debt is hard, and there’s limited appetite for it in public markets, giving private credit an edge.

Yet even here, competition is tough. Direct lenders must deploy their bulging pools of capital, meaning they're having to compete for the same relatively risky deals. The extra return over interbank rates available on low-ranking private debt has come down to around 7 percent recently, according to one banker. That implies returns can still exceed 10% or so, but only by taking more risk.

The bigger private credit shops are best placed to cope with adversity. Some can tap more liquid sources of funding, giving them access to cheaper capital. Blackstone has brewed up a private credit CLO, for example, while other players have their own listed lending arms, like Ares Capital, allowing them to issue relatively cheap bonds. Ares has also gotten more involved in the syndication process, as evidenced by its role helping to dole out part of a public-private loan package for Bain's $4.5 billion take-private of Envestnet.

Another avenue is to partner more explicitly with banks. Apollo recently struck a $25 billion partnership with Citigroup, covering direct lending and private credit more broadly, which should give Marc Rowan’s asset manager a continued flow of future buyout deals to finance. It’s generally easier for the bigger direct lenders to seal these kinds of cooperation agreements, since they have the funds to make it worth banks’ while.

The giants of private credit also arguably have bigger fish to fry. Apollo is feeding the balance sheets of insurers and annuity providers, including one that it owns, with credit sourced from new realms like asset-based finance. Rowan reckons that opportunity will easily eclipse the size of the traditional direct lending market. KKR, Blackstone and others have different versions of the same basic idea. Other large players, like Ares, also manage public loan funds, meaning they should benefit even if deals keep moving away from the private market.

That means the smaller players will feel the worst of the pain in the new, leaner years. The minnows are already struggling: the top 10 private debt funds took over half of all new capital raised in 2023, according to Preqin. Those outside the top 50 saw their share collapse to 9% from 24% the year before.

Still, the big beasts can’t escape the reality of lower yields. Even as they’ve diversified elsewhere, the largest players are still sitting on vast amounts of money dedicated to direct lending. Investors have poured $138 billion into private credit overall this year, Preqin says, outstripping pre-golden era years like 2019 and 2018. With public markets roaring again, anyone hoping for a repeat of the recent stellar returns will be disappointed.

Updated 10:37 IST, October 11th 2024