Published 22:01 IST, August 2nd 2024

Airlines’ margins head to lower cruising altitude

British Airways owner IAG reported second-quarter results on Aug. 1. Revenue came in at 8.3 billion euros, up 7.8% year-on-year.

- Industry

- 3 min read

SAF travels. In one sense, airlines are flying high. Lobby group IATA recorded a 9% year-on-year jump in global passenger demand in June, and Europe’s big six listed carriers – Ryanair, easyJet, Wizz Air, IAG, Lufthansa and Air France-KLM – all reported annual traffic growth in the most recent quarter. Yet they have a cost problem – and it could get worse.

Healthy revenues and weak profits have been a recurrent theme among European airlines. UK-based easyJet was one exception, though Ryanair boss Michael O’Leary told Reuters he thought this was helped by easier prior year comparisons. At Air France-KLM, revenue rose 4.3% year-on-year in the second quarter, but its operating margin fell 3.1 percentage points as costs crept up. Ryanair, announcing last week a 46% year-on-year fall in net profit, also sounded the alarm on ticket prices: it had to cut fares some 15% to fill aircraft, while Lufthansa and Wizz Air also said they foresaw pressure on “yields” – revenue generated per passenger per mile flown.

So far, so predictable. Amid soaring travel demand, an excess of pilots and cabin crew during the pandemic has turned to a shortage, meaning they can extract hefty wage increases. Meanwhile, delays from both Airbus and Boeing in delivering new planes to airlines have proven a double whammy: carriers spent time and money hiring and training staff for aircraft that didn’t arrive, while the slack had to be picked up by older jets that are less efficient and require more maintenance.

Unfortunately, the green transition could hike costs further. Offsetting carbon emissions, acquiring more efficient aircraft and making aviation fuel cleaner all costs money. Take sustainable aviation fuel (SAF). Using fuels made from sustainable feedstocks such as food waste rather than hydrocarbons is by far the most plausible way of decarbonising air travel. That’s why the UK and EU have introduced mandates that, from next year, say that 2% of supplied jet fuel must be SAF. By 2030 those figures will rise to 10% and 6% respectively. The problem is that SAF can cost three times as much as traditional jet fuel. Air New Zealand, for its part, on Tuesday abandoned a 2030 emissions reduction target, citing delays in the delivery of new, more efficient aircraft and steep SAF costs.

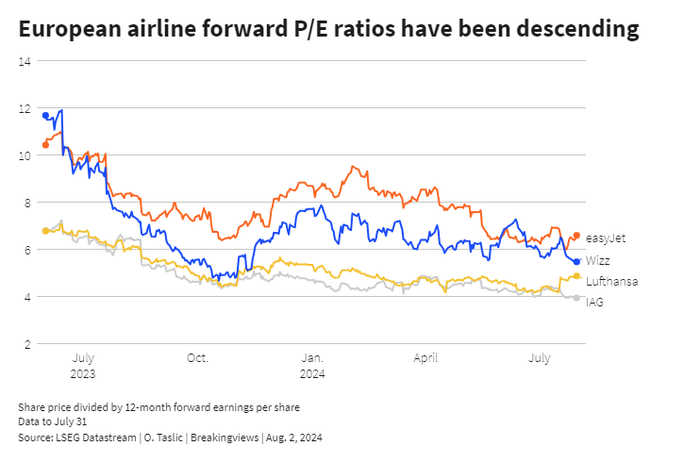

Airlines could try hiking prices, as carriers from Lufthansa to Norwegian Air have proposed. But that could hit demand. Alternatively, despite IAG shelving on Thursday a plan to acquire the rest of Spain’s Air Europa, airlines could cut costs through consolidation. Yet absent concerted efforts from governments to incentivise more production of green fuels, the most likely endgame is that airlines just make less money. Steadily declining earnings multiples over the last year suggest investors are already strapping themselves in.

Context News

British Airways owner IAG reported second-quarter results on Aug. 1. Revenue came in at 8.3 billion euros, up 7.8% year-on-year. Operating profit was 1.2 billion euros, down 0.8% but ahead of analysts’ consensus forecast. Passenger numbers came in at almost 32 million, up 6.1% versus the previous year. For the full year, the group said it expected strong demand for travel, and maintained its guidance of raising capacity 7%. It said non-fuel unit costs were expected to increase slightly overall in 2024, and also announced a return to paying a dividend. IAG also scrapped its attempt to buy the 80% of Spain’s Air Europa it didn’t own, citing concerns about the regulatory environment. IAG shares were up 5% at 168 pence at 0730 GMT on Aug. 2.

Updated 22:01 IST, August 2nd 2024