Published 12:55 IST, October 15th 2024

Putin’s economic resilience rests on war addiction

Compared to the dire forecasts made at the time, Russia’s economy has performed well since it invaded Ukraine in February 2022.

- Economy

- 6 min read

Sturdy yet weak. Russia’s economic growth has exceeded expectations since President Vladimir Putin’s decision to invade Ukraine in 2022, despite punishing measures by the West. But the performance is due to massive military spending, coupled with sanctions-busting and the redirection of commodity exports to friendlier countries. This war addiction is Moscow’s key financial vulnerability.

Compared to the dire forecasts made at the time, Russia’s economy has performed well since it invaded Ukraine in February 2022. After a 1.2% fall that year, GDP rebounded to grow 3.6% in 2023 and is on track to expand 3.2% in 2024, according to the International Monetary Fund. Russian households saw their real wages – net of inflation – increase by 7.8% last year. And sectors beyond the reach of Western sanctions, such as services like hospitality or domestic tourism, are booming.

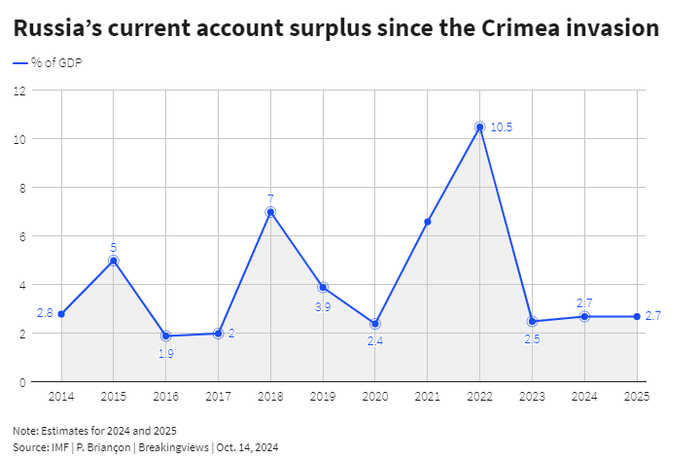

This surprising prosperity is due to three main factors. The first is Russia’s capacity to adapt to sanctions. Moscow has been targeted in some way or form since Putin’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, and its adaptability improves with time.

One example is the surprising boom in European exports to former Central Asian Soviet satellites, which seem to indicate that some Western companies have found a detour to keep sending goods to Russia despite sanctions. German exports to Kazakhstan, for example, more than doubled between 2021 and 2023, according to the U.N. Comtrade database. This seems to have little to do with the Central Asian country’s sudden appetite for Teutonic engineering: within the same time span, as it happens, Kazakhstan’s exports to Russia jumped by an astounding 40%.

Russia can also rely on China’s appetite for its oil and gas, while Beijing can provide it with some of the components it can no longer buy from Western firms. But while trade between the two countries jumped by 26% in 2023 – and although China is Russia’s largest trading partner – flows have slowed this year. Russia finds it difficult to clear payments as Chinese banks worry about being targeted by U.S. sanctions for dealing with Putin. According to Reuters, the two sides may soon resort to barter trade deals.

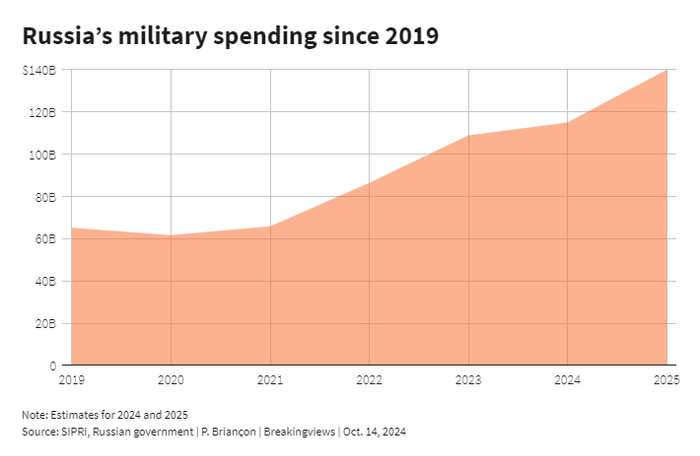

But the largest factor by far behind the resilience of the Russian economy is Putin’s massive military spending since the war began. The Russian president last month ordered a new round of mobilisation to build an army of 1.5 million servicemen – the second largest behind China – up from 1 million before the war.

And although Putin promised a year ago that military spending would not have to increase in 2025, his government has just published budget plans for 2025-2027. Part of them is classified as secret, but independent Russian analysts estimate that defence spending would jump by almost 25% next year. It would then amount to 13.2 trillion roubles ($140 billion) or more than 6% of the country’s GDP . That’s three times the level NATO countries target, but still way below the 18% to 20% level the Soviet Union was spending on defence during the Cold War years.

This huge increase in spending has not yet created a major fiscal problem. The budget deficit remains at a reasonable 1.7% of GDP this year – compared to the EU average of 3.5%, and 6.5% in the United States. And the government can so far finance itself through taxes on oil and gas, supplemented by windfall levies on some of the country’s major companies and banks in the name of national mobilisation.

Looking beyond the next two or three years, however, the picture darkens. The surge in government spending has powered the economy in 2023 and the first few months of this year, but the overheating may be starting to cool off. The central bank reported last month that a few indicators are pointing to “more moderate growth” in the third quarter. The same report also noted the economy’s longer-term challenges. They include inflation running at 9% a year, which is forcing Governor Elvira Nabiullina to run a very tight monetary policy. Interest rates rose again last month and are now at 19%.

With borrowing costs at such high levels, lending by banks to businesses or households is expected to slow down just as the government is trying to increase corporate and income taxes. Furthermore, Russia is facing labour shortages, aggravated since the beginning of the war by a significant emigration of skilled workers. The unemployment rate has fallen to less than 3% of the working age population, according to official statistics.

The second limit to Russia’s counterintuitive prosperity is that its current growth does not prepare the economy for challenges ahead. Because of Western sanctions, it is reduced to manufacturing goods – in particular military equipment – lacking in technological sophistication. As two economists noted 10 years ago, the best metaphor for the sanctions-induced growth model now seems to be the Kalashnikov automatic rifle – cheap, robust and low-tech.

Finally, the rise of military spending – now 40% of the state’s budget – means that social spending is being squeezed for the third year in a row, and investments in areas such as education and healthcare are also suffering. Putin’s popularity may dive if pensioners take a hit, and the whole Russian economy will struggle if it fails to improve productivity and growth through public investments. The country is now stuck in a model that economist Vladislav Inozemtsev has characterised as one of “growth without development”.

With ever-higher military spending on mass production of unsophisticated equipment, Putin seems to be preparing Russia for a long war of attrition – when the belligerents try to wear out their enemy, instead of aiming for quick and decisive battleground victories.

But that strategy would make it difficult for Moscow to bear the costs of a more intense and sophisticated conflict. That could happen if Europe is able to tighten its sanctions against Moscow or at least plug the many holes of its current regime.

Putin can hope that the Russian economy can muddle through, at least as long as he keeps competent liberals in charge at the Finance Ministry and central bank. In the longer term, though, the economy’s challenge will be to come down to normality once it can no longer depend on its military spending fix. Whenever that happens, however, a radically different geopolitical context might also help Russia cope with the withdrawal symptoms.

Updated 12:55 IST, October 15th 2024