Published 14:19 IST, July 8th 2024

Labour ‘open for business’ stance faces early test

Financiers have reasons to be sanguine about the left-of-centre Labour’s election success.

- Economy

- 3 min read

Business time. Global capital is set to provide an early test for Britain’s new government. Keir Starmer’s landslide victory in Thursday’s general election means international investors will soon find out whether his Labour Party’s claims to be “open for business” hold water. A series of potential flashpoints may provide some early pointers.

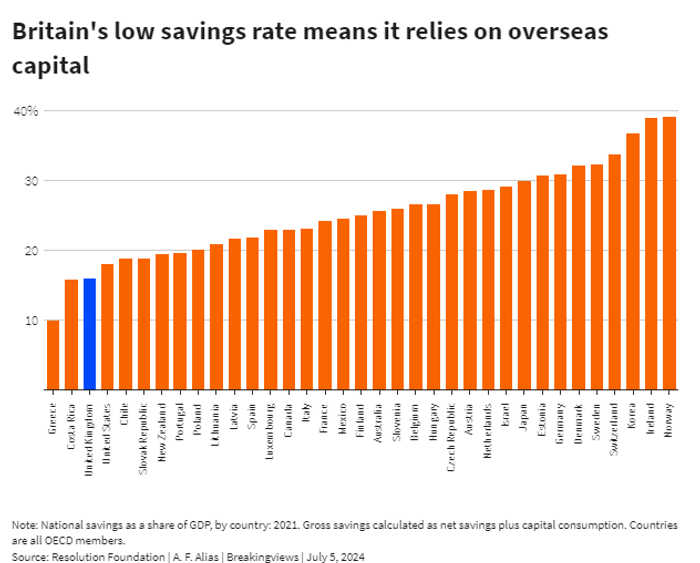

Financiers have reasons to be sanguine about the left-of-centre Labour’s election success. Bankers believe Rachel Reeves, Britain’s likely new finance minister, will be no more hostile to overseas investors than the previous Conservative government. The country’s low savings ratio means the government needs to attract foreign direct investment if it is to meet Starmer’s goal of spurring growth.

Besides, Labour has all the powers it needs to ward off unwanted buyers. The National Security and Investment Act, passed by former Prime Minister Boris Johnson in 2021, earmarks 17 sectors where the government can step in if it dislikes a merger or even a minority investment.

Still, Starmer can expect some headaches. Take Thames Water, the UK’s biggest water utility with regulated assets worth $20 billion, whose holding company recently defaulted on its debt. Given the UK’s strained public finances, the government might welcome a foreign investor prepared to pump in billions of pounds. But while Labour’s shadow business secretary Jonathan Reynolds has said he does not favour nationalising the company, left-leaning lawmakers may demur.

Meanwhile, Mexican billionaire Carlos Slim may want to up his recently acquired stake in $18 billion UK telecom operator BT, which currently stands at 5%. Daniel Kretinsky is pushing ahead with his $4.6 billion agreed offer for International Distribution Services, which owns the Royal Mail national postal service. The Czech tycoon’s pledges to protect terms and conditions for workers, which Reynolds guardedly welcomed in May, are not as robust as they could have been.

One of the unknowns is which potential allies Labour will embrace. David Lammy, Labour’s likely foreign secretary, has pledged to deal with “the world as it is”, suggesting a readiness to take further investment from Gulf states like the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia. Even so, high-profile acquisitions by, say, Saudi’s $925 billion Public Investment Fund could cause political anxiety. Starmer could woo Chinese electric vehicle manufacturers like the $93 billion BYD to create jobs and help Labour’s decarbonisation targets. However, that would risk annoying the United States and European Union, which in 2021 collectively accounted for two-thirds of Britain’s stock of inbound FDI.

In July 2016, shortly after the Brexit referendum, new Prime Minister Theresa May waved through a $32 billion takeover of UK chip designer Arm by Japan’s SoftBank. Many British politicians later regretted that decision. Starmer can expect similar tests. Being truly open to business will require Britain’s new prime minister to tread a fine line.

Updated 14:19 IST, July 8th 2024