Published 14:46 IST, November 4th 2024

Global banks are nearing peak regulation

Dimon, whose bank is the world’s largest with a market value of $630 billion, is not alone

- Economy

- 5 min read

Basel summit. Sixteen years ago last month, Jamie Dimon was summoned to Washington. There, Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson presented the JPMorgan chief executive and the heads of eight other large U.S. banks with a non-negotiable proposal: accept up to $250 billion in capital from the federal government. The move was part of an unprecedented and coordinated attempt to save the global banking system from collapse. It also marked the beginning of an overhaul of financial regulation that, a decade and a half later, is still not complete.

This week, though, Dimon declared he had had enough of new bank rules. “It is time to fight back,” the 68-year-old, the only one of the nine CEOs from 2008 still in the same job, told the American Bankers Association. “We don't want to get involved in litigation just to make a point, but if you're in a knife fight, you better bring a knife and that's where we are."

Dimon, whose bank is the world’s largest with a market value of $630 billion, is not alone. Across the developed world, bank executives are pushing to limit - and in some cases reverse - rules introduced since 2008. Though previous attempts to resist the regulatory onslaught largely failed, there are good grounds for believing that banks are approaching peak regulation.

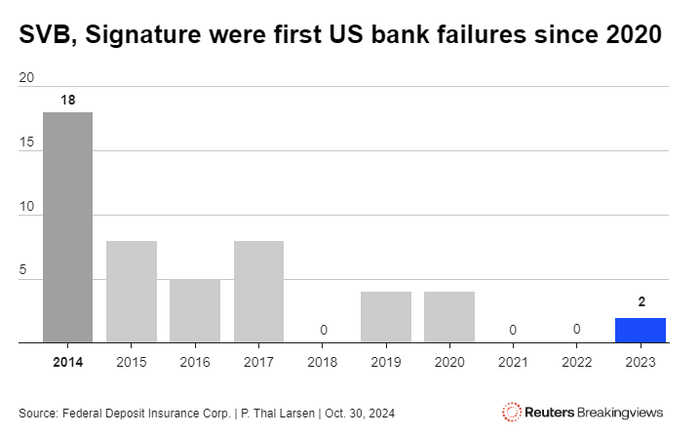

The first reason is that recollections of the crisis have faded. Banks are no longer the fragile beasts that would have toppled over in 2008 without taxpayer support. Lenders absorbed the shock of the Covid pandemic in 2020, and most large banks also emerged unharmed from the market turmoil of March 2023, when several regional U.S. banks failed and Credit Suisse had to be rescued by its Swiss rival UBS.

Andrew Bailey, governor of the Bank of England, told an audience in Washington last week that memories of crises recede over time. “I can observe this happening with the global financial crisis fifteen years or so on. I do get people telling me that ‘you have solved that one so we can relax’.”

The second reason is that banks face intense competition from private credit providers and buyout firms. Much of this is by design: after 2008, regulators explicitly wanted to shift riskier activity to institutions where reckless behaviour would do less harm. Regulators are also shifting their focus. The BoE is subjecting 50 institutions to what it calls a system-wide exploratory scenario, where the central bank asks them to simulate a shock to see how it ripples through the markets.

The third factor is that politicians who initially blamed banks for the economic costs of the crisis are now more sympathetic to the notion of a tradeoff between regulation and growth. Watchdogs in turn face accusations that their rules are out of line with other jurisdictions. Swiss bankers have criticised government plans to impose tougher capital requirements on UBS because it could make the industry less competitive. The BoE plans to shrink the period over which senior bankers must defer bonuses from eight years to five.

Meanwhile, banks have ramped up their lobbying efforts. U.S. lenders spent much of last year arguing against a package of rules known as “Basel Endgame”, which American regulators had adapted from global guidelines. They even created television ads urging Congress to act. The pressure paid off: In September Michael Barr, the Federal Reserve’s top bank cop, announced a set of diluted proposals.

This is hardly a bonfire of regulation, though. Many watchdogs are still implementing new directives. In the European Union and United Kingdom, the final set of Basel rules is not due to take effect until 2026. Regulators are also busy enforcing compliance with new rules - and punishing firms that fall short.

Yet the global regulatory edifice remains fragile. U.S. watchdogs have yet to agree on a common approach to Basel. The U.S. Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation is resisting the Federal Reserve’s watered-down proposals, Reuters reported in September, citing three people with knowledge of the matter. The standoff looks set to drag beyond next week’s presidential election. If former President Donald Trump returns to the White House, the regulators he installs could dilute the proposals further - or even ditch the Basel framework altogether.

This prospect alarms rule-setters. “An open global financial system requires global prudential standards,” Erik Thedéen, governor of Sweden’s Riksbank and chair of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, warned in Washington. “Failure on this count could result in regulatory fragmentation, regulatory arbitrage and a potential ‘race to the bottom’ leading to a dilution of banks' resilience.”

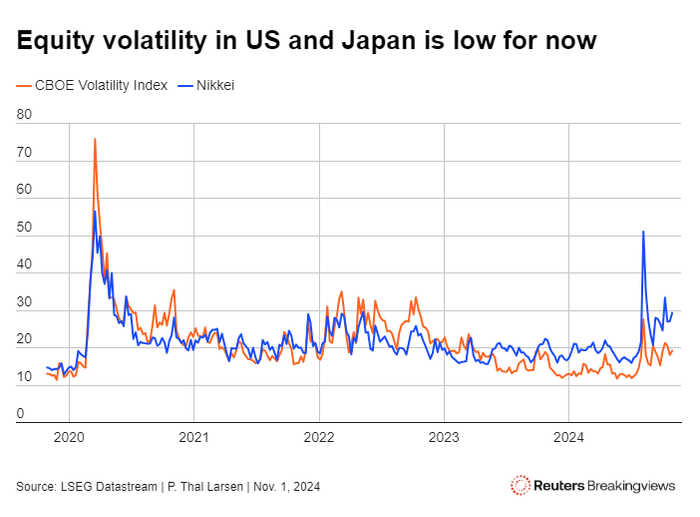

Policymakers have good reasons to be concerned. While volatility in markets remains relatively low, this is at odds with the unpredictable direction of inflation and interest rates, the International Monetary Fund points out in its latest Global Financial Stability Report. Increased geopolitical risks could also produce financial shocks. Given these uncertainties, banks arguably need even bigger buffers.

Some parts of the post-2008 overhaul also remain unfinished. Despite extensive efforts to design tools for safely winding down failing banks, Swiss regulators balked at using their powers to tackle Credit Suisse. Last year’s crises also revealed new vulnerabilities in banking: depositors yanked online funds from Silicon Valley Bank in a matter of hours.

Most big lenders do not want to dismantle the post-crisis regulatory infrastructure. Roughly equivalent global rules make it easier for international banks to operate across borders. Besides, the tower of regulation constructed since 2008 is an effective barrier to upstart fintech firms hoping to disrupt the banking industry.

Even so, policymakers should heed the lessons learned by their predecessors in 2008. Klaas Knot, president of the Dutch central bank and head of the Financial Stability Board, recently reminded an audience in Washington that financial stability is the foundation of government policy. “If financial stability is gone, as a government you can forget about the other policy priorities. You will spend most of your time drawing up rescue plans for an economy in free fall.”

Updated 14:46 IST, November 4th 2024