Published 18:41 IST, June 1st 2024

Change is coming to UK’s macroeconomic policy

Labour leads the governing Conservative Party by more than 20 percentage points.

- Opinion

- 5 min read

Labour of shove. “Change”. The single-word slogan under which Britain’s opposition Labour Party has chosen to fight the upcoming general election is certainly succinct. Judging by the opinion polls, nothing more is needed. Labour leads the governing Conservative Party by more than 20 percentage points. Yet when it comes to macroeconomic policy, change is hard to find. The party’s economic manifesto is instead characterised by conspicuous continuity. This position will be hard to sustain.

Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer Rachel Reeves has pledged not to tinker with the independence of the Bank of England and promised that the central bank’s 2% inflation target is sacrosanct. Her sole flirtation with novelty is a pledge to add fighting climate change as a supplementary objective. Even that is a revival of a tweak first made by then-chancellor Rishi Sunak in 2021.

There’s not much change at the Treasury either. Labour has ruled out increases in any of the government’s three largest sources of revenue: personal income tax, national insurance contributions, and value-added tax. Public spending, meanwhile, will remain subject to the same fiscal rule used by the current government, requiring public debt to be falling as a proportion of GDP at the end of a rolling five-year forecast period. So similar are the macroeconomic prospectuses of Reeves and her Conservative counterpart Jeremy Hunt that some analysts have christened their shared vision “Heevesianism”.

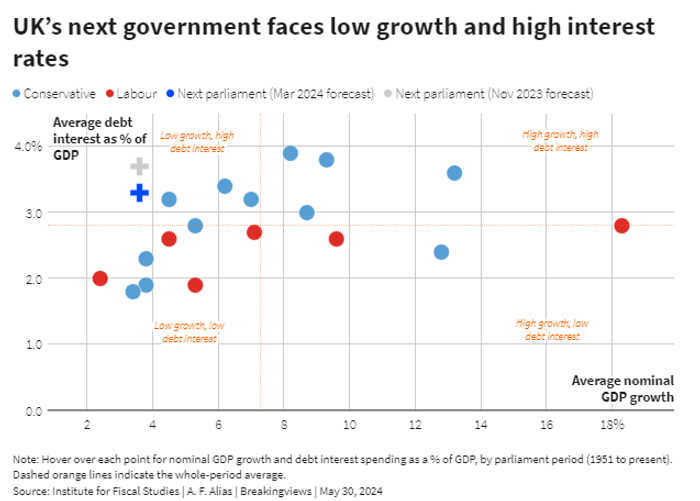

Labour’s commitment to the current policy mix is even more surprising given that impartial observers reckon Britain’s next government is highly unlikely to hit those targets. In its recently completed annual check-up on the UK economy, the International Monetary Fund dismissed current departmental spending plans as implausibly austere. The IMF predicts taxes will need to rise significantly or welfare payments decline sharply if the fiscal rule is to remain intact. The Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) puts the same point differently. The only hope for the Heevesian consensus rests on either upside surprises to growth or downside surprises in interest rates. “For a Chancellor with a goal of reducing debt as a fraction of income, things have arguably never been so bad,” the think tank says.

How did Labour arrive at this strange combination of a headline promise of transformation with an underlying commitment to more of the same? There are three possibilities.

The first and most cynical explanation is that it is an electoral gambit. Labour is so tantalisingly close to power that it has adopted what might be called a “Ming vase” strategy. Like a terrified curator transporting a priceless ancient ceramic across a highly polished floor, the party is focused on minimising any chance of a slip-up as it tiptoes towards polling day.

On this reading, Labour does not really believe in the status quo, and investors should prepare for surprises after the election. There are certainly precedents for that. One of Labour’s first acts after the 1997 election was to grant operational independence to the Bank of England, a policy that did not appear in the party’s manifesto.

Yet the chances of a sudden change of direction seem lower this time. Labour has made explicit policy commitments that stretch into the medium term. Reeves says there will be no new budget before September and has pledged not to raise corporate taxes for the duration of the next parliament. The fiscal rules, meanwhile, will be secured indefinitely by a new “fiscal lock”, with the key kept by the independent Office for Budget Responsibility. When Labour promises minimal disruption to macroeconomic policy, the party appears to mean what it says.

A second, more credible, explanation is that Labour believes the Heevesian approach is a means to an end. On this interpretation, the party is attempting to craft a modern British version of a venerable European political strategy. In the aftermath of Italy’s unification in 1871, politicians developed the philosophy of “trasformismo” – the deliberate preservation of old orthodoxies to facilitate social change peacefully from below. Labour’s analogous bet is that not rocking the macroeconomic boat will deliver the stability to focus on growth-generating microeconomic reforms.

For a party that has been out of power for fourteen years that is an understandable stance. All the same, the risks are obvious. As the IMF and IFS note, it is a hostage to macroeconomic fortune. In its original Italian incarnation, meanwhile, prolonged balancing of competing political interests eventually led to a collapse in voters’ trust and dramatic policy reversals. Investors need hardly fret that Labour’s fiscal lock will lead to the rise of fascism. But the risk that “trasformismo all’inglese” might lead to a future unravelling of UK macroeconomic policy is all too real.

The third possibility is the simplest, but also the most alarming. This is that Labour believes that sticking with the current approach will itself generate growth. That was the implication of Reeves’ first campaign speech this week, where she announced, with a telling whiff of Orwellian Newspeak, that “stability is change”.

Given the upheaval wreaked by successive Conservative governments in recent years, a steadier approach will certainly be different. Given the economic transformation demanded by global challenges, however, it is insufficient.

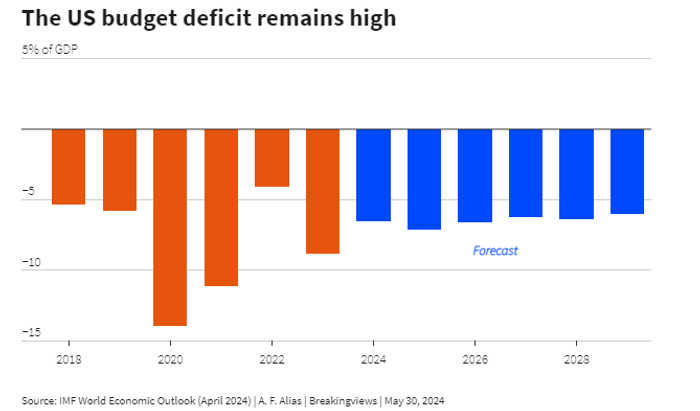

Across the developed world, the demands of battling climate change, higher defence spending, and securing supply chains in the face of deglobalisation increasingly trump accounting forecasts of debt sustainability when it comes to formulating fiscal policy. Witness the $370 billion of green subsidies in the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, passed by Congress even as the budget deficit hit nearly 9% of GDP last year.

As for monetary policy, the failure of central banks to foresee, still less control, inflation has undermined faith in the orthodox model. Just this week Isabel Schnabel, an executive board member of the European Central Bank, offered a revisionist view of quantitative easing, questioning whether the costs of central banks buying government bonds and other assets may have outweighed their benefits.

In the “age of insecurity”, as Reeves herself has called it, Labour’s commitment to continuity can’t last. Investors should therefore take Labour at its (single) word. Change is indeed coming – and the UK’s macroeconomic framework will feel it too.

Updated 18:41 IST, June 1st 2024