Published 10:54 IST, November 16th 2024

Investors ignore the law of long-term averages

The idea of mean reversion is based on the notion that, over time, both profits and valuations oscillate around a stable midpoint.

- Markets

- 6 min read

CAPE Fear. The U.S. stock market has hit 50 new highs so far this year. Investors are now anticipating tax cuts and further fiscal largesse from the next Trump administration. Yet each new peak pushes the market further away from fair value. Advocates of the principle that valuations revert to their long-term average over time anticipate dismal future returns. Unfortunately, their measures have been flashing red for so long that investors have stopped paying attention. That could prove a costly error.

The idea of mean reversion is based on the notion that, over time, both profits and valuations oscillate around a stable midpoint. In a competitive market economy, investment can be expected to rise and fall with profitability. High profits should attract more capital spending, which will eventually drive down returns, and vice versa. In theory, this effect works at both the individual company and macro level, with aggregate investment moving up and down with the market’s valuation.

There are two popular valuation measures based on the principle of mean reversion. The cyclically adjusted price-earnings ratio (CAPE), as popularised by the Yale economist and Nobel laureate Robert Shiller, compares stock prices to average earnings over the previous 10 years, adjusted for inflation. The measure known as Tobin’s Q, created by another Yale economist, the late James Tobin, looks at the market’s price relative to the replacement cost of listed companies.

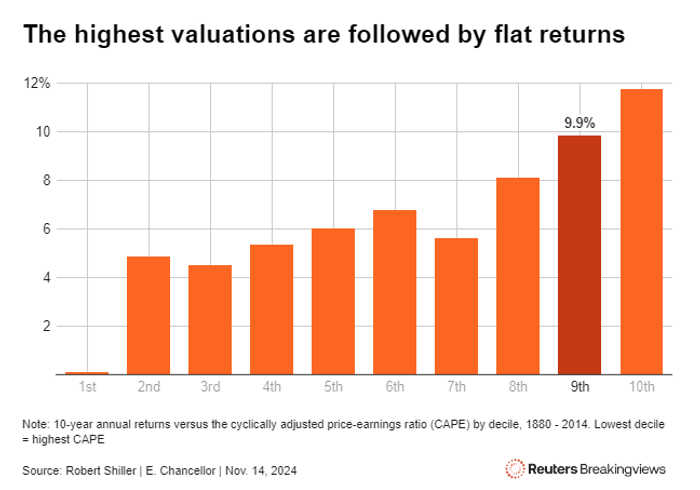

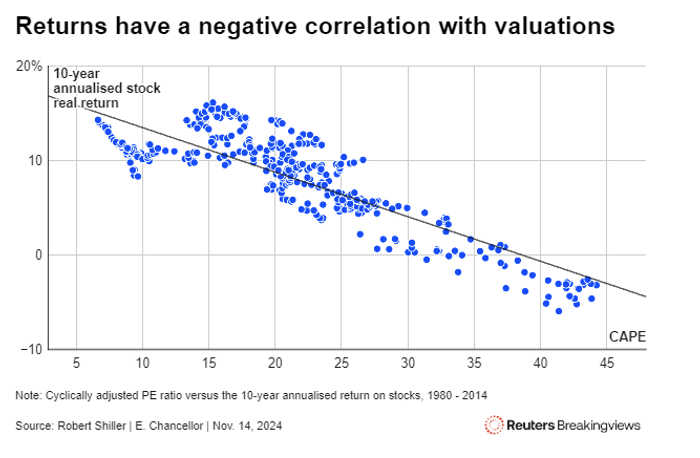

Both measures have enjoyed past success in predicting the general direction of the stock market over multiyear periods. But they are most effective at market extremes. For instance, when U.S. stocks have been valued at a CAPE that is in the measure’s cheapest decile, they have on average delivered real annual returns of 12% over the following 10 years. And after the market entered CAPE’s most expensive decile, annual investment returns over the next decade have been flat on average.

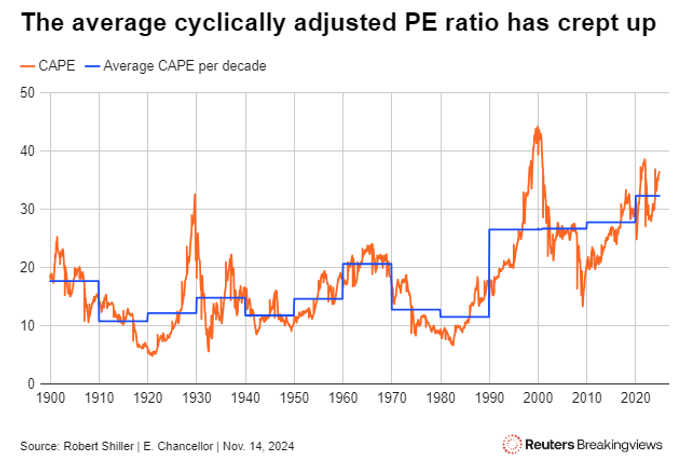

Both CAPE and Tobin’s Q correctly identified the U.S. stock market as being extremely overvalued during the internet hype of the late 1990s. The trouble is that, after that bubble burst, neither measure returned to its long-term mean, except briefly in the panic following the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers in 2008. In fact, in every decade since the 1990s U.S. valuations have climbed progressively higher. In 2017, the U.S. stock market entered its most expensive decile on the CAPE measure. Since then, American stock prices have more than doubled. No wonder investors have lost interest in mean-reverting valuation measures.

There are several explanations why mean reversion appears to have stopped working. Jeremy Grantham, co-founder of the Boston investment firm GMO (and my former boss), points to the fact that in the United States the high valuations and profits of recent years have coincided with weak investment. Net private investment is currently at around half its average level in the decades before 2000.

Grantham suggests that as American industry has consolidated it is less exposed to competitive forces. Technology behemoths such as Microsoft and Google enjoy near-impregnable monopolies. Big Tech has also been able to fend off potential competition by acquiring promising startups. If mean reversion no longer works, Grantham concludes, it’s because U.S. capitalism is broken.

Another investor, John Hussman of the Hussman Funds, believes the main driver of elevated profit margins has been progressively lower interest costs. The British economist Andrew Smithers, the co-author of a book on Tobin’s Q called “Valuing Wall Street: Protecting Wealth in Turbulent Markets”, suggests that the Federal Reserve’s large-scale securities purchases since 2008 are primarily responsible for pushing the U.S. equity market to around twice its fair value. Smithers finds a close fit between the growth of U.S. bank reserves, created by quantitative easing, and the rise in Tobin’s Q. He also suggests that enormous U.S. fiscal deficits have goosed corporate profits.

The political and financial conditions that have inflated profit margins are changing. Antitrust is no longer a dead letter in Washington. Lina Khan, the head of the Federal Trade Commission, has pursued antitrust actions against large tech firms, pharmaceutical giants, and supermarkets. The U.S. federal government has been considering whether to request a court to order the breakup of Alphabet, the owner of Google. It is not clear whether the direction of antitrust policy will change in Donald Trump’s second term as president. But Vice President-elect JD Vance has publicly expressed support for the FTC’s assault on overweening corporate giants.

Furthermore, Big Tech’s previously capital-light business model is being upended. Microsoft and its rivals, which account for an ever-increasing share of the U.S. market, are engaged in a trillion-dollar arms race to develop artificial intelligence. If this capital spending splurge does not pay off then profits and valuations will take a hit.

If Trump follows through on his threat to impose tariffs on U.S. imports, this will raise corporate costs which could potentially disrupt profits, says William Bernstein, author of “A Splendid Exchange: How Trade Shaped the World”. He points to the fact that the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930 resulted in a large contraction in world trade, knocked around 1% off U.S. GDP, and contributed to the ensuing stock market rout.

Long-term interest rates have also risen sharply. This has not yet appeared in aggregate corporate bottom lines because many companies locked in record low borrowing costs earlier in the decade. As their bonds mature, however, companies will have to refinance at higher rates. A bout of “Trumpflation” could put further upward pressure on borrowing costs.

None of these issues appear to concern investors. Nor do they appear unduly worried that the U.S. market is trading on 38 times cyclically adjusted earnings. That’s nearly three standard deviations above CAPE’s historic average and in the most expensive 95th percentile on this measure. In the past, buying stocks at such elevated valuations has not worked out well.

“As a rule,” Hussman writes, “the more extreme valuations become, the longer it has taken to get to those extremes, (and) the longer value investors have been proven ‘wrong’”, the less attention investors pay to the possibility of mean reversion. Irving Fisher – yet another Yale economist – has been relentlessly mocked for declaring in September 1929 – just before the Wall Street crash – that stock prices had reached a “permanently high plateau”. Investors who ignore the bubble-like valuations of the current market are at risk of blithely following in Fisher’s footsteps.

Updated 10:54 IST, November 16th 2024