Published 13:21 IST, December 27th 2024

Buyout Barons Will Find Ways To Douse Fire Sale

From 2017 to 2021, the industry on average offloaded about one-third of its holdings each year.

- Industry

- 4 min read

On your marks. If necessity is the mother of invention, fans of financial engineering have a treat in store from private equity titans in 2025. The buyout industry has been sitting on portfolio companies for longer than usual. The question is whether KKR, EQT, CVC Capital Partners and the rest can avoid taking markdowns when offloading their giant backlog of assets. Some innovative disposal tricks will help.

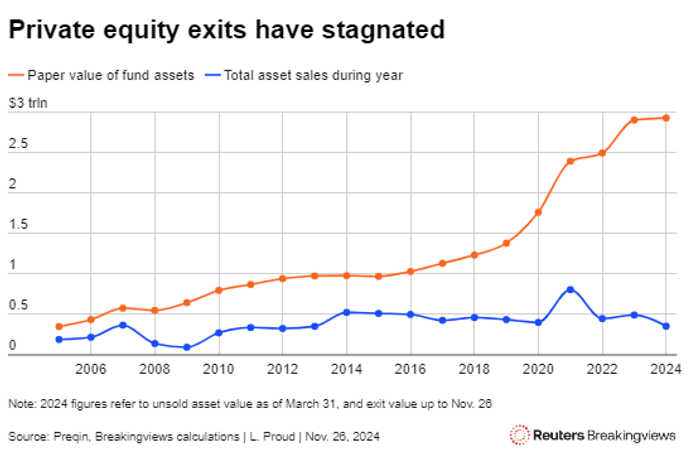

Carlyle, Stephen Schwarzman’s Blackstone and others on average sold $430 billion of investments per year from 2022 to 2024, according to Preqin – well below 2021’s record high of over $800 billion and lower even than the average for the three years before the pandemic. That’s striking since assets under management have almost doubled since 2019.

From 2017 to 2021, the industry on average offloaded about one-third of its holdings each year, according to Breakingviews calculations using Preqin data. Since 2022, exits have run at roughly half that rate, implying hundreds of billions worth of “missing” disposals.

The impetus to change that is clear. Buyout barons can’t spend much more money until they realise some cash from old stuff. That’s because investors like pension funds often rely on profits from past funds to back newer ones. From 2022 to March 2024, the sector called up $136 billion more than it distributed, Preqin data shows, meaning investors are overdue some cash.

And the shift towards ever larger deals in recent years means that buyout barons must find new homes for some very big companies. The average buyout size more than doubled between 2016 and the peak in 2021, according to Breakingviews calculations using data gathered by Bain & Co. Large disposals in 2025 may include Blackstone, Carlyle and Hellman & Friedman’s potential $50 billion initial public offering of healthcare group Medline, or Bain Capital and Cinven’s likely sale of German drugmaker Stada, worth perhaps $11 billion.

The question is whether the buyout barons’ portfolio valuations will hold. So far, many players have avoided taking big writedowns, even though stock markets stumbled after central banks hiked rates. The paper worth of Blackstone’s corporate private equity portfolio, for example, appreciated by 42% in 2021, when equities surged, but held strong in 2022 despite the MSCI All Country World Index’s 20% fall.

Industry proponents argue that such apparently rosy marks reflect private companies’ superior growth rates, allowing them to perform better than stocks. There may be some truth to that: Blackstone said that its portfolio’s revenue rose 14% in the fourth quarter of 2022. The danger, however, is that a deluge of exits in 2025 puts pressure on paper marks.

Luckily, there are tricks available to avoid a fire sale. The most obvious is to find ways to only partially sell companies by offloading stakes to new investors, rather than listing the businesses or courting other buyout funds. That avoids flooding the market.

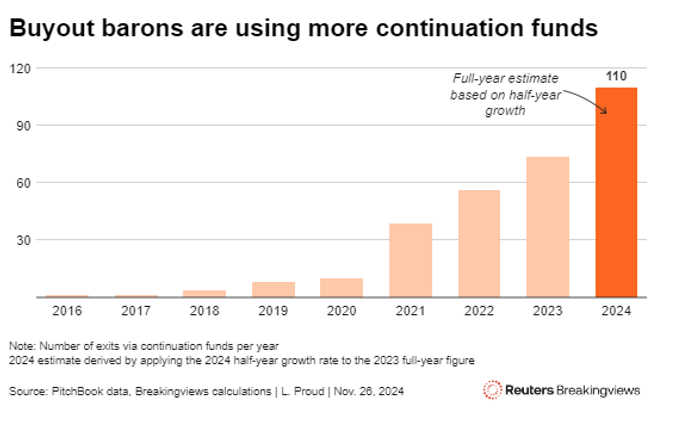

The most popular mechanism for such sales has been continuation funds, special vehicles into which private equity dealmakers can transfer specific assets. They’re usually spun as a way for managers to keep trophy businesses, while allowing some of the old investors to cash out by inviting in new capital. BC Partners showed that they can also give problematic businesses time to turn themselves around: it used a continuation fund in 2021 for academic publisher Springer Nature, which it finally listed in 2024 after it had paid down debt.

Buyout barons utilised continuation funds 49 times in the first half of 2024, up 50% year-on-year, according to PitchBook. That number will keep growing in 2025, especially with investors like Mubadala Capital gearing up to buy stakes in private equity-backed groups. Jefferies bankers estimated in mid-2024 that the total available capital to buy stakes in existing funds or buyouts exceeded $250 billion.

That huge sum will enable more novel transactions. One example could be “strip” sales, where a buyout fund sells a stake in a pool of different portfolio companies simultaneously. Deals will also get bigger and more complex. EQT’s October $14.5 billion sale of private-school group Nord Anglia Education proved the case for selling slices of very large groups to multiple investors while keeping a stake.

The Swedish firm’s boss, Christian Sinding, has proposed taking things even further, by auctioning shares in its portfolio companies to the private equity group’s clients. KKR and Bain Capital have also considered this “private IPO” idea, the Wall Street Journal reported. Such transactions are now plausible because private equity groups have thousands of institutional investors.

The net result of all this innovation is that buyout barons increasingly have ways to get money back to their investors without risking a fire sale. Financial creativity will keep the buyout party going in 2025.

Updated 13:21 IST, December 27th 2024