Published 11:04 IST, November 16th 2024

UK mistakes City liberalisation for a growth plan

UK finance minister Rachel Reeves on Nov. 14 promised a reboot of financial regulation, which she said has shackled the City’s prospects since the 2008 crisis.

- Economy

- 3 min read

Red meat. Rachel Reeves’ speech on Thursday evening must have been music to the ears of the assembled financial grandees at London’s Mansion House dinner. The UK finance minister said that post-2008 reforms had created a regulatory system that “sought to eliminate risk taking”, and pledged to unshackle the sector to boost growth. Yet thus far her reforms look vague – and risk ending up as either marginal or reckless.

The former Bank of England economist’s words echoed those of many a frustrated CEO over the past decade or so: the UK has been “regulating for risk, but not regulating for growth”; it’s time to “build a true partnership between government and the financial services sector and unlock its potential.” It’s not clear how the measures announced overnight will change much, though.

Reeves said the government will introduce a new share-trading venue for private companies, called PISCES. It looks like a formalised version of the secondary market for startups that’s already thriving in the United States. If anything, the new service may allow UK startups to stay private for longer, hurting London’s struggling new-issues market.

Other measures will cut compliance costs. These include potentially reducing the trade-reporting requirements for capital-markets businesses, and replacing the certification regime for relatively junior City employees with something less burdensome. The sector will welcome less bureaucracy, but the initiatives are hardly transformative.

More could come next year. Reeves will unveil a new financial-services growth strategy. She has also written to the Bank of England and Financial Conduct Authority to remind them that the government expects their support in helping the economy.

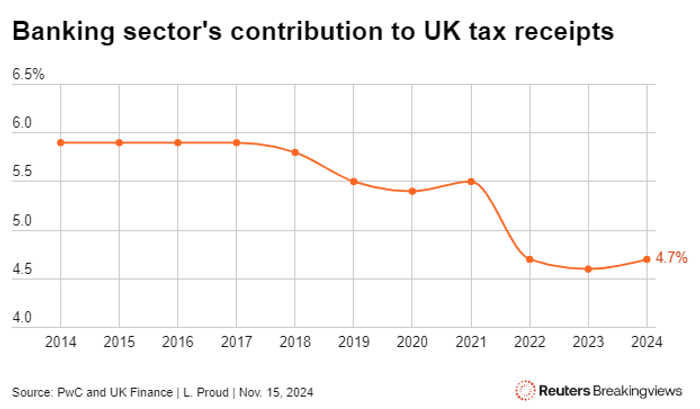

The problem is that anything meaningful for the industry, like easing bank-capital rules or other supervisory measures, could raise the risk of a financial crisis. Former Labour finance minister Gordon Brown found as much in 2008, when years of light-touch supervision prompted a wave of bailouts and subsequent recession. Deregulation arguably brings tax benefits for the government, but the numbers aren’t huge: banks contribute less than 5% of total receipts, according to research by PwC for the UK Finance lobby group.

The missing piece in Reeves’ agenda, meanwhile, is strong evidence that a freer financial sector leads to faster economic growth over the long term. The FCA looked into the question in a research note last month, but a key takeaway from the report was that academic literature is patchy. Bank of England boss Andrew Bailey, in his own Mansion House speech, noted that investment by real-economy businesses is more central to growth than whatever asset managers decide to do. The risk is that Reeves ends up making Mansion House diners feel cheerier, without doing much to supercharge the wider UK economy.

Context News

UK finance minister Rachel Reeves on Nov. 14 promised a reboot of financial regulation, which she said has shackled the City’s prospects since the 2008 crisis and stifled economic growth.

“While it was right that successive governments made regulatory changes after the global financial crisis, to ensure that regulation kept pace with the global economy of the time, it’s important we learn the lessons of the past,” Reeves said.

“These changes have resulted in a system which sought to eliminate risk taking. That has gone too far and, in places, it has had unintended consequences which we must now address.”

Reeves proposed five areas of reform: capital markets, fintech, sustainable finance, asset management and wholesale services, and insurance and reinsurance.

The government will publish a financial-services strategy early next year as part of a broader 10-year plan.

Updated 11:04 IST, November 16th 2024