Published 14:08 IST, October 21st 2024

Swiss finish would take shine off UBS’s M&A gift

Estimates that Swiss bank UBS will require another $15 bn to $25 billion in equity capital are about right, Switzerland's finance minister said on April 14.

- Economy

- 6 min read

Hit the buffers. Was UBS’s Credit Suisse acquisition the “deal of the century”? That phrase, coined by a Swiss lawmaker last year, sums up the widely held view of the wealth giant’s state-arranged rescue of its arch-rival in March 2023. The benefits for the enlarged bank run by Sergio Ermotti are vast. Yet decisions by regulators could lower UBS’s return on the acquisition from interstellar to merely respectable.

Evaluating M&A is more art than science. That’s especially true of deals involving banks, where asset markdowns and other accounting idiosyncrasies complicate the picture. A simple approach is to look at the earnings acquired by the buyer, plus any cost savings, and divide that figure by the all-in cost of the deal, including the purchase price and any restructuring costs.

At first blush that calculation looks excellent for UBS. The bank paid just $3.8 billion for Credit Suisse’s equity, according to its second-quarter 2023 filing. Analysts expect Ermotti to spend around $13 billion integrating the two firms, or $9.1 billion after tax, using a 30% rate. UBS also had to absorb extra provisions for litigation, fair-value accounting losses on the acquired assets and other hits, but those were neatly offset by the more than $17 billion boost the bank got from writing off Credit Suisse’s funky hybrid debt securities. Overall, then, the acquisition cost $12.9 billion.

In compensation, UBS gets savings which Ermotti reckons will reach $13 billion per year. After tax, that’s $9.1 billion. Divide that figure by the purchase price, and UBS is earning a massive 70% return on its investment. That calculation ignores any profit the retained Credit Suisse assets will generate. But given that the target was perennially loss-making and that Ermotti is ditching so much of the business, this does not change the merger maths.

That sky-high return figure overstates UBS’s gain, however. To start with, Ermotti has to run the enlarged bank with higher levels of equity capital, primarily because of Swiss rules that penalise lenders which have a larger market share. In February, UBS said its basic common equity Tier 1 (CET1) requirement will eventually rise to 12.4% of risk-weighted assets, from 10.6% today. Based on the bank’s balance sheet at the time, Ermotti estimated the additional capital required was about $10 billion.

Separately, UBS has removed a concession that supervisors had previously granted to Credit Suisse. In effect, this allowed the ailing lender to ignore valuation impairments at its subsidiaries when calculating the parent bank’s capital. Bringing Credit Suisse into line with UBS’s stricter treatment, Ermotti has said, adds about $9 billion to the capital requirements.

Those two additional add-ons are arguably part of the cost of UBS’s acquisition, since they suck up scarce capital resources. Add them to the purchase price, and the return on investment falls below 30%. That’s less spectacular, but still impressive.

There could be more to come, however. Swiss authorities are mulling an overhaul of the way the country’s lenders fund their international subsidiaries. For Ermotti’s group, these so-called foreign participations include UBS Americas Holding LLC and UBS Europe SE.

Current requirements allow the parent to fund its holdings in these subsidiaries with about 40% debt, meaning the underlying assets effectively have two layers of leverage – at the overseas unit, and again at the holding company. Finance Minister Karin Keller-Sutter could remove that loophole next year. She has said that could in theory boost UBS’s capital requirements by another $15 billion to $25 billion.

Assume UBS has to set aside a figure at the top end of that range and add it to the overall cost of buying Credit Suisse. The bank’s return on investment drops to 16% - still respectable, but not much reward for such a large and complex acquisition. Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria has said it is hoping for a 20% return on invested capital if it manages to buy Spanish rival Banco de Sabadell. UniCredit CEO Andrea Orcel would be solving for a minimum 15% return on investment from any possible deal with Germany’s Commerzbank, a person familiar with the matter told Breakingviews.

Admittedly, this analysis leaves plenty out. The writedowns UBS took on the acquired Credit Suisse assets may be reversed if Ermotti hangs onto them and they mature at their original face value. Ermotti could arguably mitigate the effect of a bigger capital requirement by closing even more Credit Suisse divisions.

Yet there are risks, too. It’s possible that Credit Suisse’s historic legal problems could prove more painful than UBS expects, or that the integration hits a snag. There’s also the opportunity cost to consider. A month before the shotgun marriage, analyst forecasts compiled by Visible Alpha foresaw UBS generating $24 billion of earnings between 2023 and 2025, excluding the effects of one-off charges. Now, the enlarged bank looks set to bring in about $8 billion less than that, based on current Visible Alpha data and last year’s profit excluding M&A quirks. The gap partly reflects restructuring costs, but also Credit Suisse’s operating losses and missed revenue opportunities.

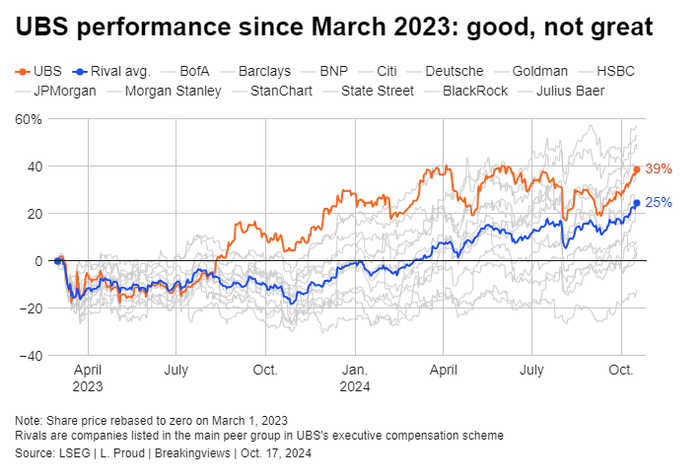

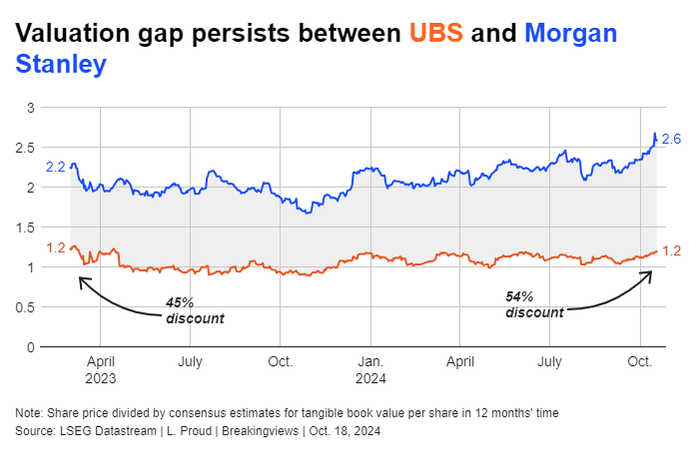

Investors are also withholding judgement. At the start of March 2023, weeks before the deal, UBS traded at 1.2 times its expected tangible book value for the coming 12 months – a 45% discount to Morgan Stanley, using LSEG Datastream figures. Today, Ermotti’s bank trades at roughly the same multiple but its U.S. wealth management rival has surged, widening the gap to 54%.

This mixed report card will doubtless influence the next bank CEO who answers a distress call from the country’s finance minister. They will be acutely aware that governments and other agencies can subsequently move the goalposts. The Swiss bank is not the first to experience this. JPMorgan boss Jamie Dimon later regretted the U.S. bank’s decision to rescue troubled Bear Stearns and Washington Mutual during the 2008 financial meltdown, stating in 2015 that the two acquisitions accounted for 70% of the bank’s $19 billion bill related to toxic mortgages.

UBS’s Credit Suisse purchase came with far more generous terms and seems likely to end up as a net positive for shareholders in even the bleakest scenario. But the higher Swiss regulators push up its capital requirements, the more the next would-be bank rescuer will drive an even harder bargain.

Context News

Estimates that Swiss bank UBS will require another $15 billion to $25 billion in equity capital are about right, Switzerland's finance minister said on April 14, according to a report by the Tages-Anzeiger newspaper. Those orders of magnitude, which come from analysts’ estimates, are plausible, Karin Keller-Sutter said in an interview. Keller-Sutter was speaking after the Swiss government set out proposals to tighten regulation for banks deemed "too big to fail", particularly UBS. UBS CEO Sergio Ermotti said on May 7 that the bank was already adding almost $20 billion in additional capital as part of the deal, before any future requirements.

Updated 14:08 IST, October 21st 2024