Published 21:15 IST, September 6th 2024

Private equity spoils of war bound to spread again

Private equity leaned on lumpy earnings from buying and selling companies, property and other assets, anathema to the common desire for consistent growth.

Advertisement

War horse. The metamorphosis from “private equity” to “alternative asset management” has been lucrative. To make the transition, buyout barons followed a new north star: fees. The surprising winner, at least for now according to public investors: Ares Management, a firm whose namesake is the Greek god of war. With further shifts underway, however, any grip on the valuation mantle is tenuous.

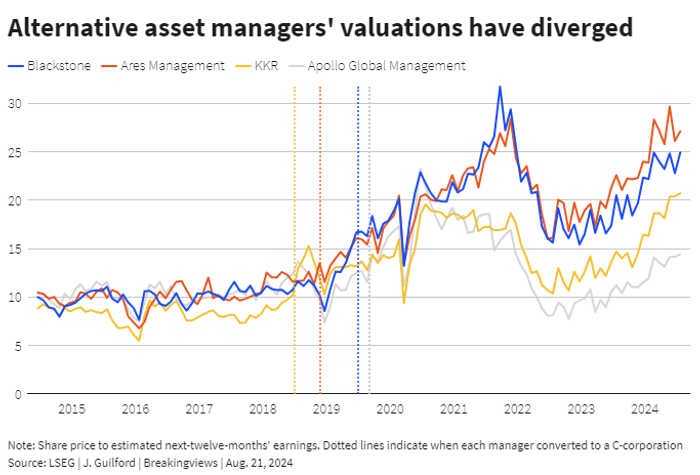

After Fortress Investment Group led a wave of peers onto stock exchanges in 2007, just before the global financial crisis struck, industry performance broadly underwhelmed. Blackstone, KKR and Ares traded at about 10 times year-ahead earnings projected by analysts, according to LSEG, roughly in line with investment banks such as Morgan Stanley and a discount to larger, rival fund managers like BlackRock and T. Rowe Price.

Advertisement

Private equity leaned on lumpy earnings from buying and selling companies, property and other assets, anathema to the common desire for consistent growth. Worse, the buyout shops went public as partnerships, whose reporting and tax oddities scared away prospective backers.

They have since transformed. Starting with KKR in 2018, the firms became corporations, opening the door to a wider crop of investors. A massive shift also emphasized collecting steady income from managing money instead of carried interest, or the profit generated from investments. In 2016, management and advisory fees accounted for less than half of Blackstone’s revenue. Seven years later, the proportion surpassed 80%.

Advertisement

When coupled with the varied strategic approaches – for example, Blackstone aggressively courted smaller investors while Apollo Global Management merged with insurer Athene – valuation multiples increased, albeit unevenly. Ares, at nearly 28 times, trades at a 10% premium to Blackstone, and even larger ones to KKR and Apollo.

The divergence reflects valuation methodologies that prize steady income, prompting the race to turbocharge fees. Not every private equity decision maximizes the multiple, including the hefty balance sheets of KKR and Apollo. Even so, there is a clear sorting mechanism to determine which cash flows are, in fact, most advantageous. For the time being, shareholders value characteristics that favor the use of debt and going lighter on assets.

Advertisement

Started in 1997 with a focus on lending, Ares is prospering partly thanks to the rise of private credit. Regulation discourages banks from holding onto buyout loans and a patchy market for parceling them out to investors has increased the appeal of borrowing elsewhere. What began as a niche backing takeovers of less than $1 billion is far larger today. So-called direct lenders financed three-fifths of buyouts in 2023, a record, per consultancy McKinsey.

Money has poured in. Assets in direct lending grew to some $850 billion last year, roughly 29 times more than in 2010, research firm Preqin reckons. And since loans extended by Ares and others are tied to a floating benchmark interest rate, higher borrowing costs also help, even as they simultaneously curb private equity deals. Since late 2023, quarterly returns for private debt have outpaced those of buyouts, MSCI data show.

Advertisement

The benefits flow, to varying degrees, across the industry. Top shops are diversified. Blackstone has a big private credit operation; Ares raises chunky buyout funds. The composition varies, though. Blackstone’s credit and insurance segment accounts for nearly one-third of the more than $1 trillion it manages, while credit makes up nearly three-quarters of the approximately $450 billion at Ares.

Such differences add up. For example, traditional closed-end funds, which lock up money from pension plans, endowments and sovereign wealth funds for a set time vary their fee structures. In private equity, management fees typically switch on after a fund is capped. In private credit, they’re levied on capital once deployed. It means accumulating money is more important for equity, while in credit it’s finding deals. Today’s climate – in which fundraising has dipped for two consecutive years, according to Pitchbook – favors credit.

The pace of harvesting fees matters enormously for publicly traded private equity firms. Barclays analysts value Blackstone’s fee earnings, stripping out those related to performance, at a multiple of 52 times, versus just 12 times for income from investing. In 2023, Ares derived some 92% of its profit from fees, a little more than at Blackstone.

Hazards abound, however. Higher borrowing costs, for one, put companies under greater stress. Ares boss Michael Arougheti has said he expects defaults to rise. Moreover, at listed business development companies – essentially, publicly traded lending units such as subsidiary Ares Capital – an increasing share of interest is being paid in-kind, meaning not in cash. Among all BDCs covered by Fitch Ratings, such payments increased from less than 4% of total interest and dividend income in 2019 to 9% in the first quarter this year.

With the U.S. Federal Reserve clearly poised to lower interest rates in September, the burden should begin to ease. But such a shift invites other concerns. The current higher base rates translate into higher coupon payments for lenders, boosting their odds of beating the return thresholds promised to investors. Meanwhile, banks that backed away from leveraged loans are now creeping back, increasing competition.

The established private equity crowd is also ready for a revival. Blackstone, KKR and Apollo are back to investing their record-size war chests. This, too, benefits Ares, which lends against many of their deals. No debt investor, however, can hope to capture the potential upside of equity deals done at bargain-basement valuations at a market nadir.

Short-term payoffs from savvy dealmaking pale next to bigger changes afoot. Blackstone rocketed to an eye-popping valuation by attracting workaday wealthy investors into funds like BREIT, which targets real estate, and a non-listed BDC called BCRED. These are huge pools of capital. Ares Capital, with $25 billion of investments, is the largest public BDC, yet BCRED is twice as big. They also pump out fees; BREIT alone probably accounted for nearly a fifth of Blackstone’s total fee earnings at its peak, according to Breakingviews calculations. It is now rolling out similar products in areas such as traditional buyouts.

Elsewhere, Apollo’s decision under CEO Marc Rowan to unite with Athene has hurt its valuation. Insurance earnings, as a rule, fetch conservative multiples. Ultimately, though, investors may come to appreciate Apollo’s ability to print safer, asset-backed loans that capture a bigger piece of the credit markets.

All this has led to grandiose assessments of what’s at stake. KKR sees an $11 trillion opportunity from tapping individual investors; Blackstone has pointed to a number 8 times bigger. Ares, Apollo and KKR have all pegged private credit as a $40 trillion market.

Beyond the eye-popping numbers, there’s sharp-elbowed jockeying to seize the spoils. With so much to fight for, the top valuation spot will again be up for grabs.

21:15 IST, September 6th 2024