Published 12:48 IST, December 23rd 2024

China will wield big mop to clean up property mess

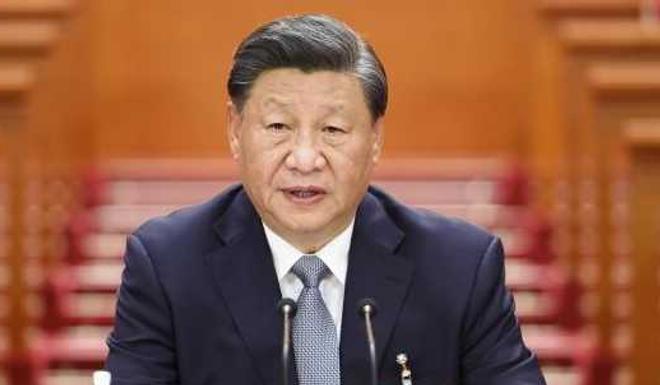

Most economists agree that Xi cannot reinvigorate growth without first stabilising the property market.

Taking stock. China is struggling with a property glut. Millions of unsold homes are weighing on real estate valuations and undermining President Xi Jinping’s efforts to stimulate the world’s second-largest economy. In 2025, expect the authorities in Beijing to step up by creating a housing policy “bad bank”.

Most economists agree that Xi cannot reinvigorate growth without first stabilising the property market. The scale of the problem is anyone’s guess. Researchers at Goldman Sachs estimate residential inventory would amount to 93 trillion yuan ($13 trillion) if developers completed all projects currently under construction. That’s equivalent to eight times the value of homes sold in China in 2023.

The overhang has weighed heavily on a sector which at its peak accounted for about a quarter of China’s annual economic output. Big developers like China Evergrande and Country Garden have either gone bust or stopped investing in new projects. New home prices fell 5.9% in October, the fastest pace in a decade, and the 16th consecutive month of declines, according to National Bureau of Statistics data. The slump has crimped spending in Chinese households, many of whom count property as their main source of wealth.

Beijing has made attempts to stop the rot. In May 2024 authorities unveiled measures to encourage local governments to mop up the glut and turn it into affordable housing. Yet according to domestic news outlets progress has so far been disappointing. A 300 billion yuan relending programme set up by the People’s Bank of China is equivalent to less than 3% of annual home sales. Indebted local governments are also reluctant to participate, because purchasing vacant units from private developers at large discounts would risk depressing prices further.

A more decisive step would be for the Chinese state to step in as a buyer of last resort. This is what other countries have done during housing crises. Following the Great Depression, the U.S. government in 1938 set up the Federal National Mortgage Association, known as Fannie Mae, to reinvigorate the real estate market by buying up mortgages from banks. During the euro zone crisis, Spain set up an asset management company called Sareb to acquire distressed loans to property developers from Spanish lenders.

A similar housing policy bank could provide the same kind of boost for the People’s Republic. It would allow local governments to mop up millions of unsold homes across the country, and selectively turn them into affordable housing, either for rental or sale. By controlling the pace at which property is released on the market, the new bank could help regulate prices. It could also build and operate a land reserve by buying uncompleted projects from cash-strapped provinces and cities.

Such a bailout would be costly. Economists such as Huang Qifan, an adviser to the China Finance 40 Forum think tank, have put the sums required at anything from 50 trillion to 70 trillion yuan. Yet if the bank’s creation quickly revived confidence and averted a deeper housing slump, the state might only need to chip in a relatively small proportion of this.

When Xi first came to power in 2013, his administration was also grappling with a property market downturn. Citing ministerial officials, state media outlets at the time suggested “basic conditions” were in place to set up a housing policy bank to tackle excessive inventory. Eventually the central bank stepped up instead, injecting more than 3 trillion yuan of liquidity between 2015 to 2020 to effectively subsidise the “destocking” of new apartments.

Ironically that move helped to inflate the property bubble, which eventually burst in 2020 and left behind a much larger property mess. In 2025, the Ministry of Finance will need to wield a big mop to clean it up.

Updated 12:48 IST, December 23rd 2024